To Confront a Portrait in the New Year

A Moment of Reflection Inspired by Walt Whitman

Written by Sophia Diaz

The new year brings with it the possibility of change, a season ripe with resolutions and retrospection. In 2017, our access to image making and consumption will continue to be grand. Most of us unceremoniously hold a master key to an infinite catalogue of images and data in our pocket. The ease with which we can capture an image on our phone and immediately send it out to the trolls and coddlers of the Internet world makes it possible for us to mass-produce ourselves like never before in human history. With this access comes the responsibility and burden of how we choose to make our Selves to the world. Who do we find as we scroll through the detritus of these amassing images of ourselves?

In order to proceed in our self-reflective musings, we need to go back to the 19th century, to the person who gave Americans the liberty and manner to explore notions of Self at all. Back to the pivotal moment that inextricably connects the literary and photographic representation of self. We need to go back to that serendipitous union of Walt Whitman and the daguerreotype.

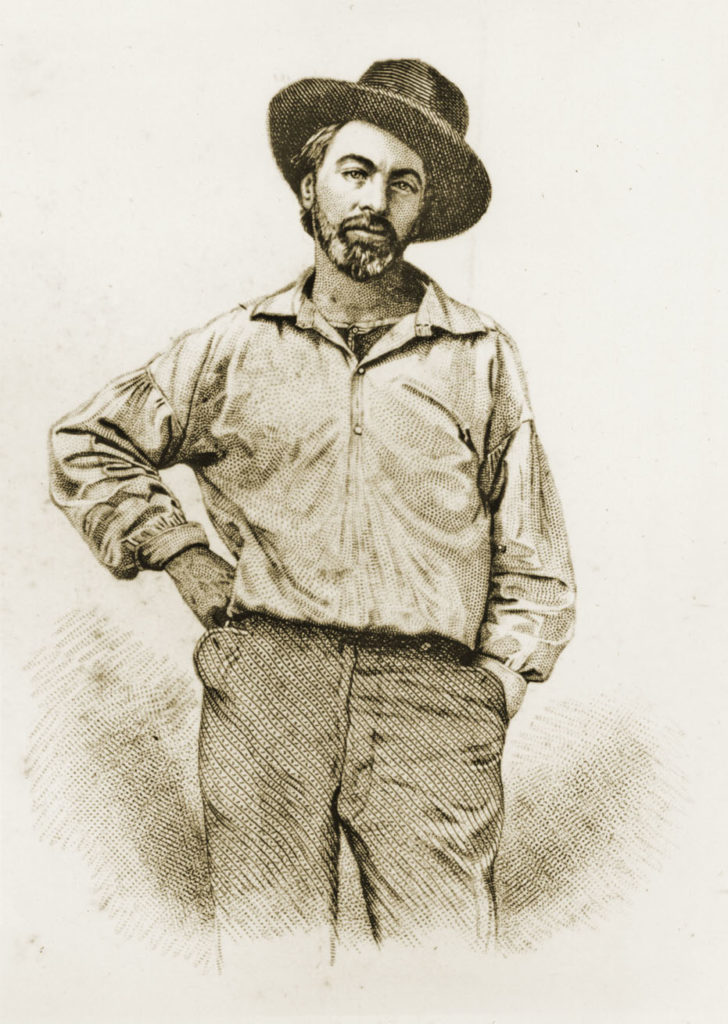

Daguerreotype portrait made of Whitman, age 29. Photo courtesy of the Walt Whitman House, Camden, New Jersey.

In the mid-1800s, Walt Whitman (poet, editor, genius, and general eccentric) wrote a new kind of poetry, grounded in a profound notion of self and elevated by a visceral description of the corporeal. Considered the father of free verse poetry, Whitman wrote himself out of the confines of meter and rhyme, opening his poetry up with an intimacy that felt as if he were sharing a conversation with his readers. His work provided a complete portrait of human life with catalogues of imagery ranging from ejaculate to an autumn landscape to trash. His critics deemed this frank perspective crude and most people did not appreciate his quest to democratize poetry, his hope to instill within the medium a more honest semblance of reality.

At the same time as Whitman crafted his literary portrait of the candid Self, the daguerreotype made its way to America. The daguerreotype was the first publicly accessible photographic process…Ever. By treating a polished sheet of silver-plated copper with chemical fumes that make it light sensitive, exposing this to light, and finally developing it with mercury vapor —voilà, a moment captured in time with precision never before attainable! Before the daguerreotype, oil paintings were the dominant way to render the representation of a subject. Now, it is hard for us to imagine a world without the Internet, let alone a world without photos, but the daguerreotype was the very first of its kind. The images were considered to be exact copies of the subject, free from the creative interpretations of the limner and their painted portraits. Whitman described his aesthetic preference: “I find I often like the photographs better than the oils—they are perhaps mechanical, but they are honest. The artists add and deduct: the artists fool with nature.”

Of all his many portraits, Whitman declared this photo, “the best picture of all…I was at my best—physically at my best, mentally, every way.” Age 44. Photo courtesy of the Alderman Library, University of Virginia.

Flash-forward about one hundred and seventy years and we cannot deny the creative control that a photographer holds over the representation of their subject. The numerous and powerful ways in which a photographer can manipulate the reality of the subject (via lens, type of film, aperture, etc.) are undeniable. Acknowledge our anachronistic perspective and then try to imagine the magnitude of this visual paradigm shift in the 19th century. Imagine looking from oil painting — a textured plane with brush strokes visible to shatter the illusion of the subject’s reality, to daguerreotype — a glossy specter of the subject that seemingly floats in a dimension all its own. Imagine the thrill and terror of being the first generation to witness your own aging through images of your immortally youthful past. Imagine how severe and important these images must have felt. Whitman describes the experience of looking at a portrait, “An electric chain seems to vibrate… between our brain and him or her preserved there so well by the [photographer’s] cunning. Time, space, both are annihilated, and we identify the semblance with the reality.”

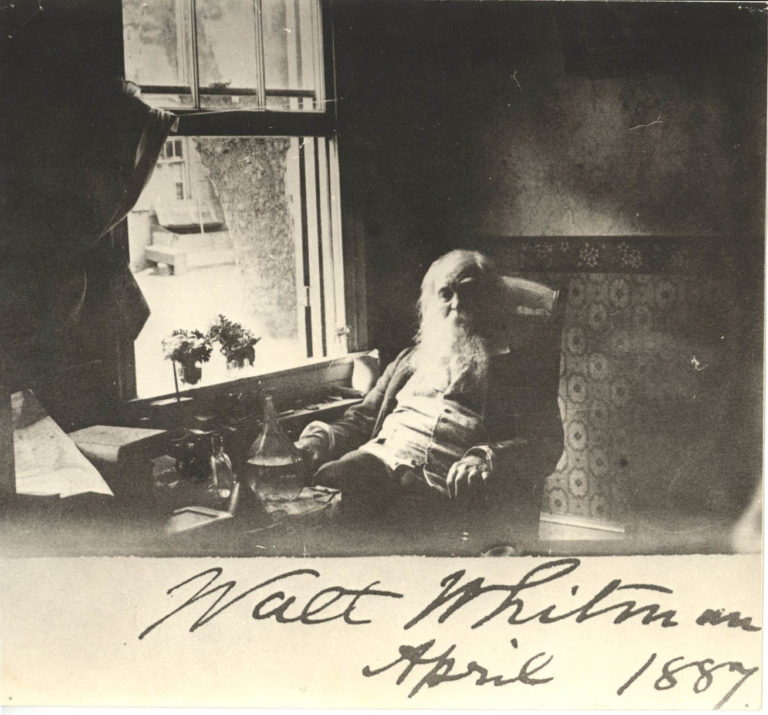

Whitman in the sitting room of his home, age 68. Photo courtesy of the Alderman Library, University of Virginia.

Whitman fell deeply in love with the symbolic and aesthetic possibilities presented by photography. Ed Folsom best describes this creative synthesis, “[Whitman’s] catalogues brought reality hurtling into poetry with the same speed that photographs were cataloguing reality.” Just as Whitman distilled candid lived experience in his poetry by including the lewd, mundane, and magnificent details of life, so too did photography establish a condensed, potent particle of life itself, unedited, full of detail. While these processes are undoubtedly parallel, it is important to recognize the ways in which they resist each other. If photographs, for Whitman, ‘annihilate’ time through their mechanical nature, then his poetry recreates time through emotion, re-instills the fullness of time through visceral experience.

The original frontispiece to Leaves of Grass, engraving done by Samuel Hollyer based from a daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison, age 35. Photo courtesy of the Bayley Collection, Ohio Wesleyan.

Whitman’s magnum opus, Leaves of Grass, provides the most salient example of how photography informed his literary process. In the summer of 1855, Whitman independently published the first edition of Leaves of Grass. This small collection of only 12 poems did not include the author’s name in print. Instead, Whitman chose to be represented visually in the frontispiece by an engraving made from a daguerreotype portrait. It wasn’t until the third edition of the book that he decided to print his named on the cover or title page at all. Throughout the numerous editions of Leaves of Grass, Whitman continued to include a photographic representation of himself, updating the portraits as he aged. Over the span of a 35 year period, Whitman continued to revise and publish the collection, which grew exponentially from 12 to 400 poems, releasing over six vastly different editions. Leaves of Grass was a life-long creation for Whitman, something not to be finished until he himself could no longer live to write it again. The last edition was published two months before his death. With each iteration of Leaves of Grass, Whitman re-imagined the project to find a new relevancy for his readers and for himself. In many ways, Leaves of Grass functioned as the literary portrait of the man, analogous to the many photographic portraits Whitman affectionately collected of himself.

Perhaps Whitman would have been the first in line for the newest, smartest phone. Perhaps the possibility of holding a camera and publisher in our pocket is his dream of democratizing poetry and images in one: a tweet and a selfie. Perhaps the excess of this access would be disturbing to him, a perversion of the potential held by the daguerreotype. As fascinated by the images of himself as he was, in his later years, Whitman began to question whom exactly the photographs represented. He found himself overwhelmed by the various selves that surrounded him in the form of his younger portraits, “It is hard to extract a man’s real self—any man— from such a chaotic mass—from such historic debris.” These musings of “Self” preservation hold equal potency in the hyperreal spaces that we occupy today. While Whitman was the most photographed writer of the 19th century, he earned this title with only about 150 portraits. How many images of your Self exist in our nebulous reality right now? Hundreds? Thousands? If Walt Whitman could not handle the scope of 150 portraits, how do we propose to manage 1,500 imitations of our Selves? How do these images represent you? What do these images take away from you? How can we further democratize our Selves in an age of simulation?

As we move into 2017, we encourage you to engage in this crisis of Self.

The final frontispiece of a rare 1892 edition of Leaves of Grass, age 72. Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Works Cited:

Folsom, Ed. “Introduction: “This Heart’s Geography’s Map”: The Photographs of Walt Whitman.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 4 (Fall 1986), 1-5.

Folsom, Ed. Whitman Making Books/Books Making Whitman (Iowa City: Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, 2005).

Library of Congress. America’s First Look into the Camera: Daguerreotype Portraits and Views, 1839-1862.

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. 1855 & 1892.