Eight Girls Taking Pictures: a novel – A non-literary review

Written by Anne Di Elmo

A novel by Whitney Otto

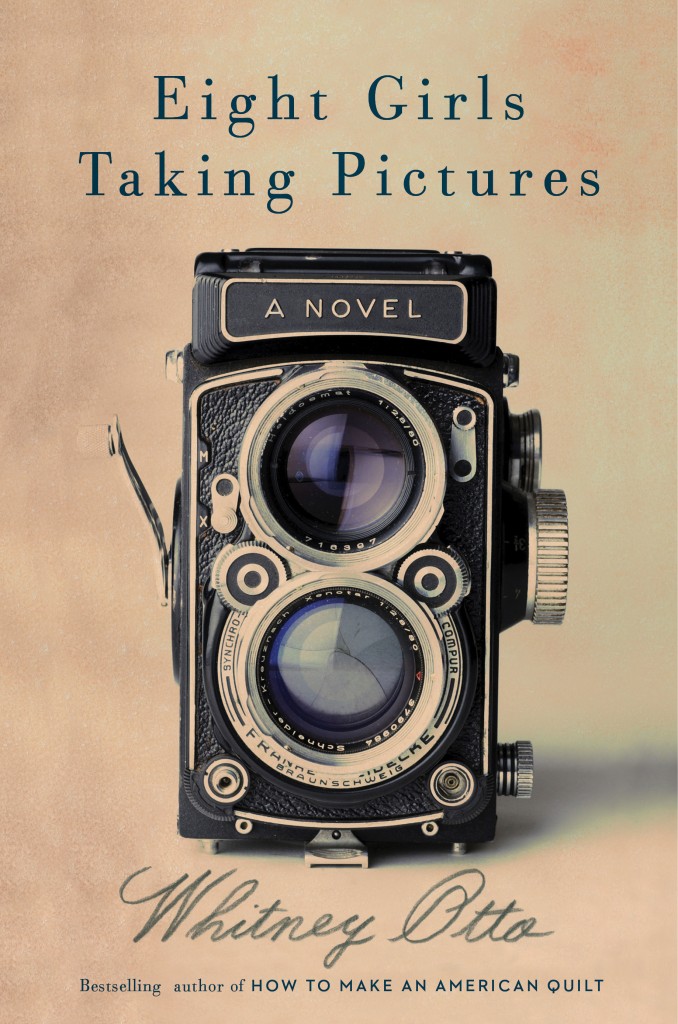

The short of it is that I love this book. It caught my attention at Powell’s earlier this year because of the illustration on its cover – an instantly recognizable one for a film photographer- a Rolleiflex. I didn’t buy it that day, but the book stayed on my mind and when I finally got my hands on it, I knew that if I should use my hard earned income on one hardback book this year, this would be it. If you’re interested, there are plenty of reviews of this book from a variety of perspectives; this is a personal review from a young photographer.

The book, described as a novel, is divided into eight stories, each one centered around a single main character. The stories focus as much on the women’s formative years as the years where photography was their profession. Ms Otto’s characters share a common trait – they are independent and very modern women who travel the world on their own, and those experiences make them ponder their role within society and in the art world, as well as their professional and personal options when they come home.

I would recommend this book to photographers and non photographers alike. It does not take a photographer to fall in love with the narrative and the ever relevant questions it raises. And while it is a book that deals with photography, it is also one that deals with art in a more universal way. Mostly, though, it is a book about women who are in love with photography and with men (or in the case of one character, another woman).

In addition, the novel is about the difficulty of being a woman in a field dominated by men and where women have to choose between forging their own path or following a path charted by their male counterparts. Amadora Allesbury , a photographer practicing portraiture in the 1910s, decides to include color in her images, a bold move in an era where black and white was more common and less experimental. She also creates her own brand of portraiture, moving away from the stiff portraits of society ladies and embracing a more unconventional style. Lenny Van Pelt becomes a combat photographer during the Second World War, by accident, after a career as a model, a photographer’s assistant and later, a fashion photographer.

The wives and mothers among them have the choice to work but sometimes opt to stay at home and educate their children. While they continue making art, it is within the confines of the home. Cymbeline makes photographs of domestic life : of her children, garden and flowers; Jenny’s most popular and controversial subjects are also her children; Miri documents the events she sees happening from her apartment window. She captures weddings, children at play, the changing seasons. Their gazes turn inward, but there is still a sense that their photographs don’t reflect the particular as much as the general. When Jenny makes photos of her children, she is not just capturing her children on film, she is showing us childhood.

Photograph by Anne Di Elmo

Several times, the character Cymbeline Kelley broaches the question of photography as a serious pursuit for men, even a career path, but a mere hobby for women, who – according to their male counterparts – make ‘pleasant’ photographs (i.e not art). This is an issue that particularly resonated with me. Cymbeline remarks that “the men only see what we do as sweet, sentimental, missing the meaning entirely as they view us as women who make photographs in our spare time. They don’t take our subject seriously because they cannot see it – even when Miri Marx writes, if you want to know what it’s like to be a housewife, I can show you. Nor do they consider the steel it takes to raise the kids, run the household, be a wife and still keep alive the artist part of you”.

In the world of serious amateur photographers, men who practice street photography or landscape photography are revered and lauded often, but women who choose to concentrate on still lives, no matter how great their skills, will be told by male photographers that their images are simply ‘nice’. Or worse, they’ll have to bear with such enlightening commentary as ‘I’ll have some of that’ about a particularly beautifully lit and composed image of food. But a man who shares some exceptionally bland street or landscape photography will be hailed as a genius by his peers.

The same goes for women photographers who make photographs of their children or of attractive female models. In this particular case, the attention of the male audience will be diverted to the attractiveness of said children or female models. ‘Cute kids!’, as opposed to ‘beautiful composition and use of light’ is a comment that is often heard.

Another element of note is that Whitney Otto shows the trajectory that her characters’ art and processes take. We follow Cymbeline’s growth as a photographer, from assistant to photochemistry student, to portrait photographer who focuses on a romantic relationship, to one who chooses to portray “domesticity as a garden, plant by plant, flower by flower, tree by tree”.

Photograph by Anne Di Elmo

One of Whitney Otto’s many skills lies in not only understanding the shifts that happen in a photographer’s style and subject – which I imagine are fairly similar to those experienced by writers – but also understanding photography as an art and a craft. She describes the techniques employed by her subjects in a manner that emphasizes not just the skills they require, but the senses they bring into play. She aptly describes, for instance, the way a Rolleiflex feels in one’s hands, the operation of its advance crank, and the act of looking through a waist level finder and composing with the image reversed in the glass. All of those gestures and feelings are familiar to film photographers (certainly to all of us at Blue Moon) who cherish the routines as much as the results.

So go buy this book and spend some time with it. Spend more time than you might otherwise on the narrative and Ms Otto’s style. Imagine the way the cameras used by her eight female characters would feel in your hands. Picture the events that led to the creation of the images she so vividly describes. And when you’re done, you should take up Ms Otto’s advice and read some of the books in the attached bibliography. Consider this your suggested summer reading list. For now go shoot some film, possibly through your old Rolleiflex, just like Whitney Otto’s characters.

Photograph by Anne Di Elmo

Find the book at these fine local establishments:

Powells