Ode to the USPS : Voices of the Harlem Renaissance

This winter we will be celebrating nearly 20 years of analog love here at Blue Moon and a critical (though often unspoken) factor in our success as a small business is our reliance on the United States Postal Service. We have customers from rural Alaska to Tokyo. We ship orders all over the country every single day! Simply put, we just would not be here without the USPS and we absolutely cannot continue without the vital services that they provide.

Beyond their affordable shipping rates, the USPS provides vital public services by delivering life sustaining medications, they employ nearly half a million people across the country, and they establish a lifeline of communication and connection for all of us during these particularly isolating times. In spite of their importance, the USPS is actively being defunded. Fortunately, there are several ways that you can help!

Get involved with the US Mail Not For Sale campaign.

Contact your senators, urging them to approve the Delivering For America Act, a bill that has already been passed in the House.

Text ‘USPS’ to 50409 to have Resistbot guide you through some streamlined actions.

Buy stamps and boost your penpal community: write your old friend from grade school, or an elder in an assisted living facility, or to an incarcerated person you’ve never met before. Typewritten letters are a particularly wonderful gift to receive. Throw in an original optical print and you’ve just made someone’s whole entire day! Luckily, we can help you out with both of these flourishes of analog love!

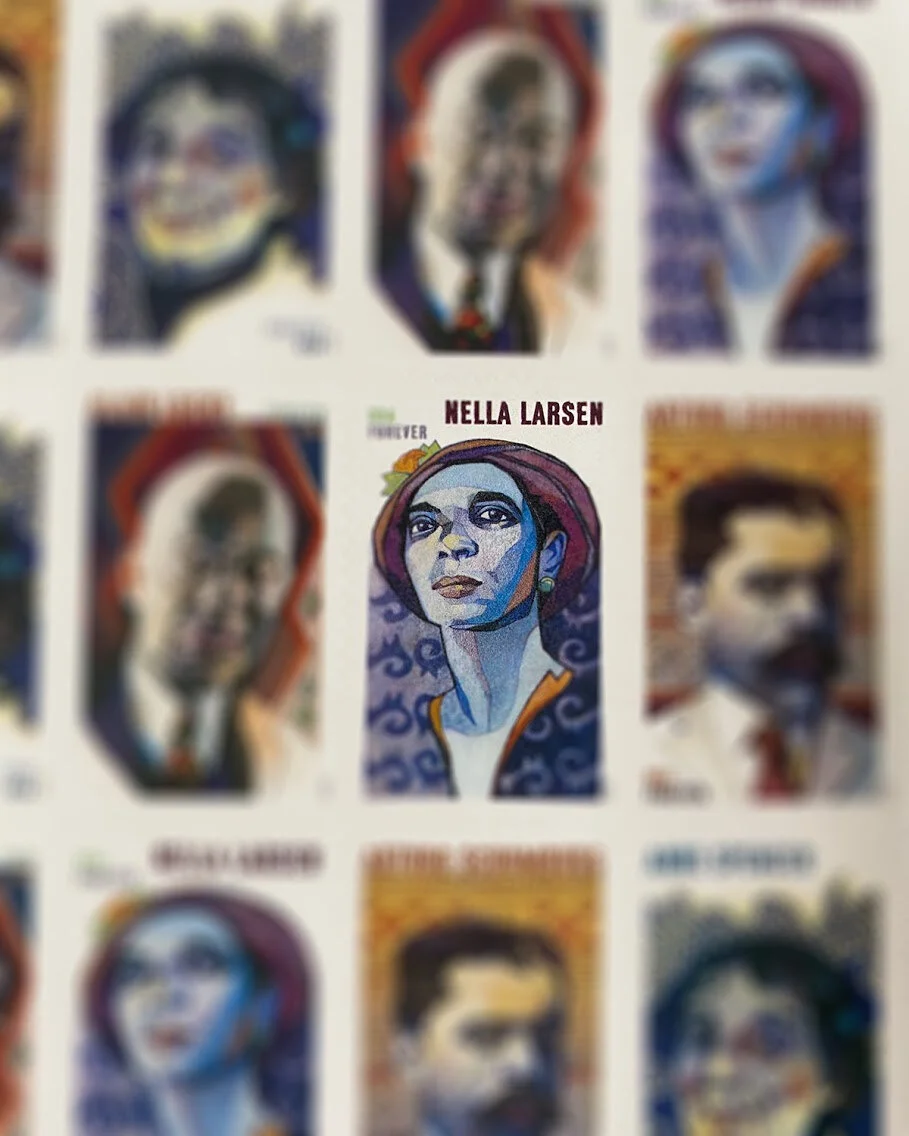

We have a lot of favorite stamps, but our latest favorite stamps were released in May of this year - they are the Voices of the Harlem Renaissance series. These stamps feature four influential artists, historians, and writers from the creative and cultural bloom that was the Harlem Renaissance.

Alain LeRoy Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke was born in 1885 in Philadelphia. His parents were both descendants of prominent Black families who were never enslaved during chattel slavery in the United States. [sidenote: his father was the first Black employee of the USPS.] Locke was the first Black person to earn a PHD in philosophy from Harvard University, and he was also the first African American Rhodes Scholar. He taught at Howard University for about 35 years and is considered to be the godfather of the Harlem Renaissance.

Locke was a philosopher, self-organized cultural producer, and a gay man. Due to his position of prominence as a professor, Locke was forced to live a fiercely protected existence. The FBI had a covert and ongoing investigation on him (as is fairly standard for leaders within BIPOC communities) and, due to the discriminatory laws against homosexuality, he was only able to be out to a very small and trusted community. Even within the confines of this persecution, he still managed to find ways to support and mentor other Black queer people within his immediate community.

One of his largest accomplishments was the curation of The New Negro in 1925, a truly multi-disciplinary, inter-genre anthology that pulled from the spirituals, the folklore, and the reality of the Black experience; elevating this experience into high art. This concept of the “New Negro,” that African-American people are the quintessential artists, pulling joy and creation from adversity, had existed long before the anthology. Locke gave new life to this concept by helping to shape an aesthetic resource that changed the conversation around being Black in the United States from “social ward” to pivotal cultural asset. He brought an interpretive context for Black artists to be better appreciated and seen. He also created the infrastructure that allowed for more corporate and institutional funding of the arts, rather than the reliance on personal patronage that was common at the time.

Nella Larsen

Nella Larsen was born in 1891, in a poor district of Chicago. Her mother was a white, Danish immigrant and her biological father was a Black man of Afro-Caribbean descent. When she was an infant, her mother remarried to another white, Danish immigrant and the couple had a child together. Larsen grew up as the only Black person in a white, immigrant family. She had no contact with her biological father, no connection with her Afro-Caribbean culture, and was othered by her Danish community in the states, as well as in Denmark.

This positionality, of being caught in the liminal space between two identities, is where Larsen stayed throughout much of her life. She felt distanced from her Danish heritage because of her Blackness. She felt distanced from the Black community in the states because she did not feel any cultural connection with those whose ancestors had been enslaved. She even felt isolated within the small community of mixed race creatives within the Harlem Renaissance because of her poor upbringing, having never finished her degree, and the fact that she had no ‘free’ Black ancestors. Many of the people of mixed race in the scene were raised in the upper middle class, highly educated, and shared an outspoken pride in having ancestors who had never been enslaved. The tribulations and the isolation brought about by being mixed race in a segregated society informed much of her first novel, Quicksand, a pseudo-autobiographical work that she described as “the awful truth.”

Larsen had many accomplishments throughout her life, two of which being her widely praised novels Quicksand and Passing. Both of these works gave voice to the often unconsidered experience of being mixed race. Her writing was raw and vulnerable and was met with vast critical acclaim. She was lauded as an up-and-coming literary success, but her writing career halted almost as soon as it began. After several years of working and creating within the scene of the Harlem Renaissance, she left.

There have been speculations that Larsen just never could overcome the isolating feelings that came with her experience of being mixed race— that she lacked the confidence to continue in her creative pursuits. Although she stopped writing, her two brilliant novels have provided and will continue to provide unending support, representation, and solidarity for so many mixed race folks. In addition to her cultural, emotional, and ideological contributions to the Harlem Renaissance, Larsen was also a skilled librarian and a celebrated nurse throughout her lifetime. She was the first Black woman to graduate from the NYPL Library School.

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg was born in Puerto Rico in 1874. His mother was a Black woman from St Croix, his father was of German descent and Schomburg identified as a proud Afroborinqueño. When Schomburg was a child in school, a teacher told him that Black people had no history because they had no heroes and had made no accomplishments. This comment became the impetus for his life work - a commitment to preserving, documenting, and curating the history of global Blackness, on the continent of Africa, as well as in the diaspora.

When he was 17 years old, Schomburg moved to New York City and became very involved with both the Puerto Rican and Cuban independence movements. He saw many parallels between these independence movements and the fight for equality amongst his community in the African diaspora. He saw both movements as rooted in a cultural response to colonization, of body and of land. He knew that the fight for liberation intersected across identities and nations and he committed himself to being a part of this fight.

In 1911 when he was 47 years old, he co-founded the Negro Society for Historical Research, in order to unite African scholars to refute racist scholarship and to amplify the telling of their own history. He firmly believed that “history must restore what slavery took away.” In 1925, his influential essay “The Negro Digs up his Past,” was featured in Alain Locke’s The New Negro. When he was 52 years old, he sold his massive collection of art, manuscripts, books, and documents of Black history to the New York Public Library. This extensive and deeply important collection later became the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. To this day, Arturo Schomburg remains one of the most influential curators of Black history.

Anne Spencer

Anne Spencer was born in 1882, in Virginia. Though her father was born into chattel slavery, both of her parents represent the first generation of Black Americans who grew up after slavery was outlawed. For most of her own childhood, Spencer was not expected to do chores or to attend the local school, allowing her unlimited play and self-guided exploration. During this formative time, she developed a deeply curious outlook and true connection with plants and nature that proved essential to her role as poet and activist.

Spencer did not learn to read until she was 11 years old, when she was enrolled in school for the first time. From this point on, Spencer used poetry to express herself creatively, to delve into philosophy and reflection. She excelled at her schooling and graduated as the valedictorian of her class when she was 17 years old. A few years later, she married Edward Spencer and together they built a home in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Their home, and the infamous garden that she cultivated there, became a pivotal place for Black intellectuals, artists, and revolutionaries to gather and organize. The home was often a detour made by civil rights leaders travelling between the North and South. In fact, her poetry career began when she hosted James Weldon Johnson, poet and leader within the NAACP, with the intention to open a chapter of the organization there in Lynchburg. While staying with Spencer and her husband, Johnson came across some of her poetry. He was so completely taken by her work that he connected her with his own publisher. Her first poem was published when she was 40 years old. Later, her work would be featured in “The New Negro,” by Alain Locke.

Spencer demanded equity for all oppressed people and was a bold advocate for Black youth. One remarkable moment of this advocacy was when she fought for the Black youth in the community to have the same access to knowledge and books as the white youth. She marched into the “whites-only” library and demanded that they open a library for Black youth... a few months later, a branch was opened in connection with the local Black high school. Spencer served as the librarian there for over twenty years.