Drinking with Jake (Round Five) – Heidi Kirkpatrick

Written by Jake Shivery

Next in a series in which Jake Shivery and a guest get pickled and talk photography.

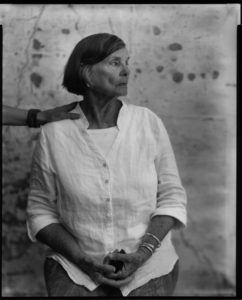

Heidi Kirkpatrick is a nationally renowned fine art photographer, mixed media artist and educator who resides in Portland with her husband, Doug. Editor’s note #1 : Please note that this interview is from 2015. Heidi retired from teaching as of June, 2016. We publish this interview now to commemorate this rite of passage. Editor’s note #2: Do not try to keep up with Heidi while drinking.

Who: Heidi Kirkpatrick with special guests Sarah Taft and Blue Mitchell

Where: Jake’s garage

When: September, 2015

What: Heidi: Chardonnay, everybody else: Bulleit Rye with a bit of ice

Jake Shivery: And here’s Heidi Kirkpatrick, my first female victim.

Heidi Kirkpatrick: Victim.

JS: I’ve been getting my chops busted by my university mentor – she’s been reading the interviews and she likes to point out: “Well they’re good, but how’s it going to be when it’s not just an old boys’ club?” So we’ll see.

HK: So we’ll see.

JS: Well – how’s your mom?

HK: Mom’s good. She just got back from visiting her boyfriend in Florida. He thinks she’s going to move in, but she thinks she’s just going to stay there ten days a month. That sounds good to me.

JS: Where is she now?

HK: She’s in Springfield, Ohio, where I was born and raised. Funny story about Mom from when she was here – you made our portrait for the second time the day before she was heading back to Ohio, and I didn’t tell her what we were doing. I didn’t want her to fret about it. She had her angry face on when we got there and said that she didn’t like the one that you made before, because in her mind she looks like she did when she was forty. I get it, I think I look like I’m twenty. I think this is natural. I brought the beautiful portrait from the first session home with me. So we’re having dinner, and she said “Can you take a picture of that picture with my phone?” So she does like it.

JS: Well, she looks great.

HK: I know. That’s what I told her. She likes being the star. Who doesn’t like being the star?

JS: In fact, probably the best portrait I had in that show.

HK: It was fun for me, for people to figure out that she was my mother, because people don’t think of me as a Lambert. My maiden name – and now my middle name. I wasn’t given a middle name, so I made my own.

JS: So you took one for yourself. In the traditional style.

HK: Yes. I’d been with Doug for three years and he is second generation American – Scottish and Irish. St. Patrick’s Day was on a Saturday and I said that if he didn’t marry me, I was taking his name anyway. It worked out – we had our twenty fifth anniversary this year.

JS: Amazing.

HK: It is. It goes fast.

JS: I have staff now younger than your marriage.

JS: So, you grew up in Ohio? In Springfield?

HK: I did. It’s a great place to be from.

JS: Any comment on the Midwestern sensibility?

HK: Well, we don’t get to choose where we’re born and raised. I had a great, fairly normal, childhood. Upper middle class upbringing. Middle child. Two older sisters – I think my parents were disappointed that I was yet another girl, but they tried again and did have a boy.

You know, when I was a kid, it was fun. You got to run around wild and get dirty and play in the pool and stay out until the streetlights came on, with no worries.

JS: That’s probably a sufficient segue into speaking about your role as an educator.

HK: Well, I say that photography chose me, and being an educator chose me, as well. Thankfully, I listened. Doug’s dad bought me a camera in 1992, said he saw something he liked in my pictures, I was making pictures of family and friends and when we traveled, like I still do.

It was in Portland where I really threw myself into photography. I met a woman who has had a huge effect on my life. I was doing a cyanotype demo at Portland State – the Women in Photography class – where I met Michal. She ended up teaching at Northwest Academy and also started a small business on SE Division. This was a gallery space and rental darkroom – a precursor to Newspace – called Safelight.

Safelight is where I did my first teaching – and it was with adults. Michal thought I should teach at NWA; I didn’t think so at the time. Several years later, I got a call from NWA offering me a temporary 5 month position teaching basic black and white darkroom at the high school level. I thought that sounded fun and interesting and I accepted the position.

I never wanted to have kids, and had not ever worked with people that age. I loved it, but it was the hardest thing I had ever done. It was very challenging and I don’t think I’ve ever had more doubt, but at the end of the five months, the kids said “don’t leave” and I didn’t. I decided to stay through the end of the school year, then I decided to graduate that class, and now, this is year twelve.

JS: How long have you been in Portland?

HK: Since ’93. Nineteen years in our house as of Labor Day. Portland has been very good for me; it’s nurtured me as an artist. It’s been a great place to be.

JS: What was it like in the nineties?

HK: Well Doug and I lived in a small apartment downtown. It was fun moving here from Dallas, Texas – but it was absolute culture shock. I didn’t have a job or a car for the first time since I was 14, and I was thirty three at the time. I hit the street with my camera. I loved those days – I had a perimeter, and could only go so far, and I worked very thoroughly within it. Our apartment became a submarine with my photography taking over, so we started looking for a bigger place.

About this time, the job that brought Doug here from Texas wanted him to move back, but we decided that no, we weren’t doing that. And we’re still not doing that.

JS: So Doug took another job.

HK: Yeah, he started working with a friend of his from college, also from Western New York.

JS: In what?

HK: “Plastics” is the short answer. Really, he just cusses on the phone in his pajamas all day long – that’s his actual job.

JS: Wow.

HK: Yeah. He’s really good at it, too. [laughs]

JS: So, you took your first picture at age what?

HK: Thirty two. It all more or less started when we got here.

JS: I’m just trying to get a sense of time line. Your first exhibit, your first sale, your first publication, et cetera.

HK: We can chronologically work through my work, starting with street photography and how images of women are used in popular culture. That was about me wandering upon the images, not creating them in the studio; working with a toy camera, and what my students would call “taking pictures of pictures”. Normally, advertisements, mannequins, being out on the street and finding the work. Most of this was from Portland, although Doug and I were traveling a lot. I found it interesting that everywhere we went – Iceland or Thailand or Mexico – I was finding the same kinds of stereotypical images of women: young, beautiful, skinny, shirts open, legs spread, which is not really, actually stereotypical. This is not really how women are. My mother doesn’t look like that. I don’t look like that. None of my friends look like Barbie dolls with perfect make-up – especially not here.

OK, so I moved here in ’93 and started taking classes right away. I audited classes since I wasn’t after a college degree, but then decided that I wanted to teach. I started my studies at Portland State with John Barna and Richard Kraft. I applied to PNCA in 1996. With my portfolio, I placed as a junior, but I still had to take all these foundation classes. Now, I was thirty five and most everybody else was 18 or 20. I wanted to do photography, I didn’t want to take drawing and theory – Richard, who was my adviser, suggested that I quit and so I did.

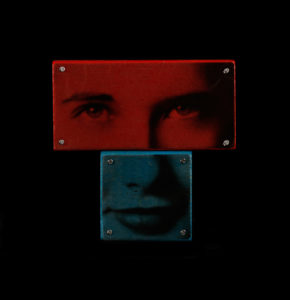

Richard Kraft had introduced me to some socio-documentary work – very politically driven. Images of people projected onto buildings, almost more of a performance piece. I twisted that concept by projecting images of buildings onto women – just to see what it looked like – and it was that work that turned into my first solo gallery exhibition, Flesh and Stone and that was ’98.

I felt the work on the walls was a little crowded – I wanted to pull out one piece, but the gallery talked me out of it, and of course, that’s the one that sold.

JS: Of course. Always the 37th frame.

HK: So this was my first big sale. A stranger paid money for something I made. That felt different. That was the beginning of my career.

Alysia Duckler had her gallery in the pearl district. The first work I showed there was called Modern Goddess. It was all studio work dealing with time – starting with seeing pictures of myself and realizing how I was aging. This work was made with hot lights in the studio using long exposures, showing some movement. I wanted to make beautiful portraits of women who did not necessarily feel that they were beautiful. Every time I would approach someone to work with, there was always something – “Oh, I’m too fat,” or “I need a haircut” or “my face is broken out” – always something along that line. This was my first exhibition in a PADA gallery. The sales were weak, not uncommon for a first exhibition.

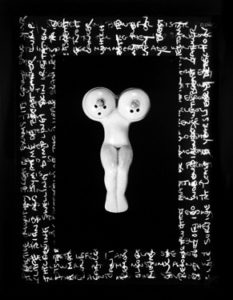

My next show with Alysia was Girlie and I sold $8,000 worth of work the first night. I mean, there’s a lot of overlap with these projects – I’m never content to work on one thing at a time. I’m a Gemini. I need more than one thing at a time. But Girlie, in 2003 and 2004, that was the first of the photo objects.

Girlie was in response to my friend Sue Boyer dying of breast cancer. We bar-tended together in Dallas. She didn’t want to have the surgery to disfigure her body and it killed her.

I photographed booby art, everything from vintage through modern day objects – salt and pepper shakers, cake pans, lighters, swizzle sticks, bottle covers, all kinds of crazy stuff. This was my first foray into mixed media. The pieces were big, hinged shadow boxes, chalkboard paint with my handwriting overlapped both horizontally and vertically – not completely obscured, but not trying to just give it away. My mother and my aunt and my sister have all had breast cancer, so I had personal experience to bring to the table.

The whole time, I’m making regular pictures too, and experimenting, moving from paper to film.

PNCA invited me to do a show of prints in 2006-ish, maybe later. Stories, these prints on paper, the last series I created on paper, were all unique images made from magazine and newspaper pages that I had been collecting for 5 years.

And all of this has relations to my life, being a woman and an artist. I work with issues about body image and about lineage and about the archetypal female relationships. But also other issues, like addiction and disease.

Science stuff – scientific illustrations and the series Specimens. I was working with the anatomy pages and female imagery – the illustrations would act as clothing or tattoos, binding or wrapping the body. This was during my red period.

And funny stuff, too. It’s not always so serious. During the 2008 crash, we needed something a little more light-hearted. There were the souvenir cedar ashtrays, with an image of women’s butts layered over a myriad of illustrations, I called this series Cigarette Butt.

But it’s always been the dress, it’s always been the female form. Just a little while ago, Doug said “Another dress?” and I said “You know what, you want to do pants, go ahead. I’m sticking with the dress.”

JS: So the dress is the representation, the reflection of the female form for you?

HK: Yes.

JS: So you’re interpreting female strength from the form of the dress?

HK: Yes. I feel there is a lot of power in the dress. Women are strong. The dress to me is representative of many different times and roles in our lives. Child, daughter, wife, mother, sister, friend, lover. Then there’s confidante, teacher, listener, forgiver and on and on and on.

JS: You have a lot of female archetypes that you are working with.

HK: There are so many. The body work stems from me having had a lot of health issues, the deconstruction of the body and putting it back together is me working the puzzle. When I was at my physical worst, the images are really bloody. There’s a lot of red, and the work has definitely become more subtle.

JS: It’s more subtle because you’re feeling better?

HK: Yes. The worse I felt, the bloodier it got. The better I feel, the more subtle and softer the work becomes.

And historical; with the 3D work, I use a lot of re-purposed antiques. I like bringing in the spirit of older objects, discarded bits of our history that I can give a new life. Block pieces, tin pieces, Mahjong tiles in ’08 – I did a series called Winning Hand – a limited edition of eight, and my first editioned object pieces, where every set was different.

JS: So you’re re-purposing all your old finds, melding them into your own ideas – where do you want these things to go? Where should they end up?

HK: In somebody else’s house. [laughs] Seriously. I make them for me but not for me to keep. Object-based work takes up a lot more space than stacks of prints.

I’m fortunate to be well represented, so the flow out is pretty good.

JS: You’ve had a pretty fast rise – I mean, I guess it’s been twenty years, but it seems fast to me. You’re all famous, now.

HK: So I started not even knowing how to develop a print, but I was immediately hooked on the magic. That was ’93, and then the first big show in ’98, but this was the first time I didn’t have a job. So I could really assert myself as an artist. I was spending thirty hours a week in the darkroom. The good old days. I wish I was doing that now. But I love teaching.

Photo Lucida 2011 was a defining moment in my career. I sold enough work to pay for my reviews and still made money. I did not see that coming. I came home after the first day, laid out my portfolio and just cried. It takes guts to throw your work out on the table – “here, you want to judge me?” I was the only person showing work that was not flat.

I tell my students – you have to have guts to put it up on the wall. Not everybody’s going to like it, and they’re going to tell you so.

JS: So there you are in 2011, and you’re being represented in Seattle.

HK: By Gail Gibson. I won’t ever forget that day. I went in with no appointment, just a referral from Ann Pallesen from Photo Center Northwest; you don’t just walk into a gallery without an appointment. It was crazy in there, the phone was ringing, the UPS guy was there, clients, et cetera. Claudia walked in and said “Sure, get your portfolio”. I opened my portfolio box, Gail and Claudia flanked me at the flat file, they looked over the work, looked at each other and said “Yes”. I remember calling my mother that night with the news and saying, “They carry dead photographers!”

Dream. Come. True.

And all this sounds great, but remember, I’ve got Doug backing me up. I mean, the sales are good and all, but I would have starved to death. Even now, I’m more or less at poverty level, if you just look at the art. I had a good year last year, but even with the teaching and the art combined, I’m still fully aware just how much I need Doug around. I used to thank him in some of my writings and or giving a talk, and he always says: “Please don’t thank me. You did it.”

Well, if I was working forty hours a week, I couldn’t physically do it.

JS: So you’re selling really well and have reps everywhere and yet you’re still at poverty level. When you’re speaking to young artists or students and trying to describe your more-or-less meteoric rise, how do you explain the path?

HK: As far as the poverty level? As far as Doug being the breadwinner?

JS: Yes, being with someone else to make your own work possible.

HK: Well, this is a very expensive game we are playing. I have said many times in the past that I have two jobs, teaching and being an artist, neither of which pays very well. It’s never been about the money. If it had been I would have quit a long time ago. Doug and I make a good team – we are equal partners in the life we have built.

As far as dealing with my students, well, I’m not the college counselor. I don’t encourage or discourage them from going to art school. I’m not trying to raise up a horde of young artists; I’m trying to show them some passion, and show them somewhere they can put it. I know how much joy photography gives to me as a person.

I hope that the students continue do some photography, but it takes other forms, too. I had a student write me from New York – and she’s not into photo anymore – but she wrote me a thank you note for instilling in her the photographic eye. She just walks around the street and sees things differently. That kind of makes me cry.

I’ve worked hard and I’ve been very lucky and I’ve been willing to throw myself out there. That’s what I tell my students. In my studio, I have a stack of rejection letters tacked to my wall. Well, eventually, I had to go to a nail, when the tack would no longer hold them. And it felt so good to jam that nail through that stack of rejections. Which I still add to.

JS: How are your students now compared to the students twelve years ago?

HK: Every year is different. It’s amazing how much one student can change the whole dynamic of the class. And the school is much different now, too. When I started, we had 60 students, and now we have more than 200. All of my students have enriched my life.

Now, let’s talk about the less glamorous part of being an artist. I have to spend so much time now in front of the computer – challenging for a black and white girl. But you have to be the marketer and handle the social media and these are all good things for me, but I simply do not enjoy sitting in front of a computer. I would much rather be in my darkroom or at my table.

I prefer the in-person modes: Photo Lucida has backed me; Portland at large has backed me. We have such a fantastic community here; better than Seattle, better than Chicago. It seems that in other cities everybody’s working on their own. Here, we like to hang out. Look, we’re friends and artists together. I don’t feel like you’re my competitor.

I came to Portland kicking and screaming; now I hope I never have to leave. I was here for years before I ever came up to your store, and as soon as I entered, I regretted not being there sooner. Same thing with Portland in general – now I go back to Dallas and wonder how I ever could have been happy there. But honestly, I have been happy everywhere I have lived.

JS: Do you want to talk about Dallas?

HK: We can.

JS: Do you want to talk about drugs and so forth? I read a bunch of interviews with you while prepping for this, and you always sort of…

HK: …touch on it. Yes.

JS: I remember a couple of years ago, watching you give your lecture at the museum, and you were quite candid. I remember thinking that it was my favorite speech because of the honesty, because you were very willing to keep it raw. You put yourself out there, in front of that particular bunch of people. Putting everything out there seems to be your super power.

HK: You were going to heckle me.

JS: Well, I was too stunned to heckle.

HK: OK, so my other life started when I was about eleven. I became a bartender at 18. There is a lifestyle that comes along with that profession, especially in Dallas in the eighties. I tried very hard to ruin my relationship. Fortunately, Doug is smarter than I am, and he kept trying.

I don’t use anymore, I pretty much stopped when we moved here. It was a wake up call. Moving here is where I found myself – staying straight and spending time alone and becoming a photographer.

Looking back, I think I was just bored in school – as a kid, back in the Midwest, in a small town of 50k people – what I really needed was something like NWA, but it just wasn’t available in Springfield. My parents didn’t do anything wrong, I was just in the wrong place, and at the time, getting high seemed like a good option..?

JS: So, can you define the wake-up call?

HK: Doug.

JS: You were already married.

HK: We were married in ’90. So we’d been married for three years when we moved here. He actually came without me.

JS: Because why?

HK: I was strung out. I didn’t want to move here. I didn’t want to leave Dallas. My brother and his wife lived there. I made a lot of lifelong friends and made a shit ton of money. But ultimately the drugs took over, things spiraled out of control, and I wasn’t twenty anymore – it was definitely time for a new plan.

JS: So what made you finally come up here?

HK: Doug is why I came here. I moved here and slept for two months. Literally. And then I started taking classes and got hooked on the darkroom. Basically, I traded one addiction for another.

JS: We’ll be mindful of the fact that your students might all read this.

HK: It’s fine. They know. It’s good for them to know.

Zero to thirty three was a whole different life. I was a different person than I am now – twenty years ago, I could never imagine that I would be doing what I’m doing now.

Moving to Portland was a very definitive line in my life. That was all before, and this is now. I loved Dallas and I loved tending bar, and I was really good at it. I made a lot of good friends, but I don’t miss it. I mean, I miss the people aspect, but it was just completely different, and I don’t regret any of it, not anymore. I used to think I wasted time, but I really had to do all of that to get here, where I am now.

JS: So you might say that tending bar informs some of the art that you’re executing now?

HK: Good question.

JS: I mean, you had this whole life, right? Then you had this cut-off point, and then became this fancy-schmancy famous artist. Pretty much right away.

HK: Well – twenty years…

JS: Yeah, well, there’s a lot of people who work twenty years and are still tending bar. Slinging coffee, whatever.

HK: Yes, you’re right. I’ve been lucky. I’ve thrown myself out there, and I’ve done the work, but I’ve also been very, very fortunate. I’m very aware of that.

JS: As you say, you need all three. But my question – would you be the artist that you are if you weren’t the bartender that you were?

HK: No. I had to do all that. I don’t see a direct correlation, necessarily, but it’s my whole life, my very winding road, that adds up to now.

JS: So your art has so much to do with female issues – I’m explicitly not saying feminism – and gender roles, and family and history – where does all this come from?

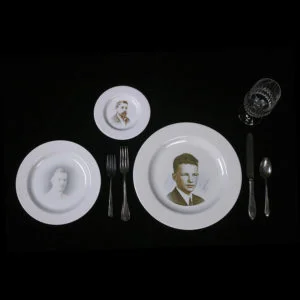

HK: From experience and from memory, which can be very selective and not always accurate. The work also comes from stories I have been told. My grandmother died when I was very young, and I’ve since been enamored with her image – haunted, in a way. I mean, she got to hold me, but I don’t remember her. I have all these images of people that I don’t know, and she’s one of them.

JS: Is your family artistic?

HK: No.

JS: Do they like your work? Does Vera [Heidi’s mom] like your work?

HK: She does. She doesn’t necessarily understand it. But that’s OK. She says: “I don’t know where she gets it.”

JS: How does your family feel about your appropriation of all the family images?

HK: They wish they owned more of it. They really do. I think they’re proud of it. I think that it’s important to them. The first photo objects that I did were all about family. In the beginning, I was photographing family photographs so that I would have a negative to work with. Eventually, I felt like I got to a stopping point and began using my own imagery in my work.

Since my dad passed a couple of years ago, I’ve been going back and working with the family imagery again. Actually working with some of the very same images. It was a very comforting way for me to start again. I had stopped working for a while; death is not easy on the living.

Dad died in May, and I had my Critical Mass award exhibition in November. I realized it’s getting close to November and I’m thinking “Holy Crap I have the biggest show of my life coming up I need to get my ass in gear.” I had the matches, the dress, and the cyanotypes, it was a huge room for someone whose work is one inch across. I never needed an excuse to work, but this timing was perfect. I ended up with the new series Dearly Departed. It’s amazing what death and the grief process can do, if you let it.

JS: You don’t have any children.

HK: Nope.

JS: What happens when you’re ninety three? Where does all this go?

HK: Well, I don’t know. We have a couple of nieces and nephews, but we also have a lot of stuff.

JS: Well, you’ve spent a long time preserving this history, and transmuting it yourself. But then what do you do when there’s nobody behind you? It’s a pointed question, by the way – I mean, I’m in the same boat. What happens to all this work when you (we) get old and die?

HK: You and I are both childless by choice.

JS: Yes, but we work so much off of ancestry. And with no potential to become someone’s ancestor.

HK: But now it’s art. Hopefully, it all goes into a collection – or collections. It’s the giant unknown, but you can’t let it bog you down.

I mean, I find all of these photo albums at the Goodwill, and some of them are really beautiful, but all of them belonged to somebody at some point. They were precious, and now they have been thrown away. Except that I found them, and I love them. All over again.

JS: Let’s talk about education a little more. Talk about principles that you teach. Name three.

HK: You mean photographically? Cause I teach more than just photography.

JS: However you want to frame it.

HK: Well, respect. That’s number one. Respect the space, respect the chemistry, respect your relationship with me, respect your camera. If you leave that camera in class, you’re in trouble. That’s yours now, and it’s your vehicle, and you need to take care of it.

Practice is two. Yes, we’re printing today, and lucky you. The only person not printing in the darkroom today is me. They all get to print, and they need to be mindful of the importance of practice.

And behavior and participation. They have to engage – they have to do photography every day that they’re in class with me.

SARAH TAFT: What grades to you generally teach?

HK: 10th-12th, mostly. I have a couple of freshman this year. The kids are great – they’re engaged, they give a shit. They take my class because they want to – it’s an elective and they don’t have to take it. The age is not as important as the engagement. And once they take my class, they usually take photography until they graduate. I get my hooks in them.

JS: I want to circle back around to this… I can’t quite find the word or words for this, but it has to do with femininity…

HK: You mean contemporary issues of being a woman.

JS: Yes, I think so.

Blue Mitchell: Do you mean in photography?

JS: Well, yes, but it’s more general that that. I don’t want to pigeonhole Heidi as if I’m saying “Lady photographer”, but I see female issues as being a real center point in the work. I just want to make sure that it’s getting enough time.

So, succinct statements about the relativity of contemporary issues of being a woman and how these relate to your photography?

HK: That sounds easy.

JS: So – you’re talking to an audience of all women about contemporary women’s issues, and making art for yourself, and being married, and basically having a patron. How do you reconcile this?

HK: Definitely an issue. I feel that it’s important to be able to express my observations. I’m not a feminist, I’m not political, I’m not a social documentarian. My work is about observations and experience as a woman in today’s world. I feel very fortunate that I get to make what I want, and do not have to make what you like.

BM: You have a very unique relationship – such obvious support.

JS: Clearly, you’re involved in an enlightened marriage. I’ve never inferred that you feel like you’re secondary to Doug.

HK: No, no – he would say the opposite. Yes, he’s the breadwinner. And he’s decided to use that to help me. Like I said, we are a good team – Team Kirkpatrick. When we hang out with people who are discussing their educations, and they’re going into forestry or social work or whatever, he’s old school – his response is always “I went to college to learn how to make money.”

Doug’s support goes well beyond the financial. He gives me intellectual and emotional support. My mother has always said that he’s the only one for me. She is right.

The most important thing is to keep working. Practice, practice, practice. Get ready for somebody to say “no”. Doug makes it possible for me to do that.

BM: What work did you show at your first Photo Lucida?

HK: That was 2011- some plates, mahjong, a lot of 3D work.

BM: I thought you went earlier than that.

HK: Oh, you’re right – I went in 2007, but it just was not right. I still took object based work, though.

I had the audacity to think that people would want to tell me things, but they actually asked me questions! First reviewer blew my mind; I was not ready, set the tone for the whole weekend. Now 2011 was a very different story – Mr. Blue Mitchell right here was my first reviewer, and it changed everything.

BM: Changed the tone.

HK: It changed everything.

JS: When you travel, do you photograph a lot, or are you more of a studio artist? Does travel have influence on your work?

HK: Not so much, anymore. Doug and I travel a lot, but I shoot much less. I used to use the Holga a lot, but I took it to Scotland and it broke, which I thought was telling. Don’t seem to need to do that right now… But the idea for the dominoes comes directly from photos made while traveling. The dominoes, which is a new-ish project, involves a lot of landscape work.

JS: We need to talk a bit about process. When you’re out shopping for objects and widgets and so forth, do you have an image in mind? Are you finding the objects and then applying an image, or vice versa?

HK: Typically, I find the object first. One nice thing about this kind of work is that it feeds my shopping addiction. I come from a long line of pickers and savers of vintage objects. I do love me a junk store. All of us, my mom and family, we love antique stores, we love yard sales, we love estate sales. You never know what you’re going to find. Sometimes, I find something and I know exactly what I’m going to do, and sometimes not exactly but I know I can use it as a frame or a substrate or a binding or I could photograph it. You’ve seen my studio.

JS: I certainly have. It looks like a museum of junk store treasures. Too clean to be a junk store, too full to be a museum. And so clean.

ST: I’ve seen the picture – it looks crazy. Just from the image, I knew that she was awesome.

BM: It’s so packed, so full of things, but it’s so incredibly organized. And not a speck of dust.

HK: You guys are just getting older – or you’re just not looking at the right places. Or you’re coming in at the right time.

JS: And the darkroom. I’ve never seen a nicer kept darkroom. Anywhere. In my whole life. It’s ridiculous.

HK: My darkroom is kind of blue right now; from making cyanotype since the summer. But I am getting ready to switch from blue to silver.

JS: And at the same time, you’re also collecting images?

HK: I also have a lot of images. I go through phases of shooting, building up a back catalog. I get obsessive compulsive, and other times – like right now – I’m taking a break. Now, I spend more time cleaning my house and sleeping in – no submissions, no marketing, just pausing. Having said that, I probably have fifty rolls of film in my house to process right now. Easy, fifty rolls.

JS: Speaking of blue. Let’s talk about Wichita.

HK: Five Alchemists was a very important exhibition for me this past February. It was nice to be recognized for the cyanotype work. I was completely blown away to have a museum show and they made me feel like a total princess. Flew me in, drove me around – paid me. Paid me. Good lord, they paid me to come in and spill my guts. The patron dinner, everything, it was like a dream come true.

Wichita Art Museum and Lisa Volpe – who is adorable – had a party at her house. Doug flew in and we had an excellent time. It was bittersweet, being the only woman among five artists, but still – always happy to represent. My work was markedly different, extremely feminine, compared to the other artists work.

JS: Want to talk about tools at all? Favorite camera?

HK: I don’t give a fuck. It’s just not important to me. The best camera is the one that’s with me. People say that I should get a better camera. Maybe in my next life.

JS: Whats next?

HK: The world keeps throwing me round things. So I’m working on a series of circular objects and images – it is going to be all inclusive: the family, the history, the female form, sewing, the cyanotypes, everything. Calling it “Full Circle”.

It’s all a giant process. I do something photographic every day. Buy, shop, develop, print, assemble. It’s good stuff.

BM: You are persistent. You work on cyanotype in the summer and silver in the winter. Not a lot of people can keep a number of projects going at the same time, all the time. I’ve always known you to be working on a lot of projects at once.

HK: That’s another Gemini trait. I like a lot of work all at once. I could put together a whole show this week if I needed to. I’m going to go home after this and work.

JS: We’re going to end right there, I think.

HK: Thanks, everybody.

JS: Thank you, and good night.