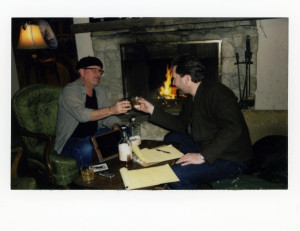

Drinking with Jake (Round Three) – Ray Bidegain

Written by Jake Shivery

Next in a series in which Jake Shivery and a guest get pickled and talk photography.

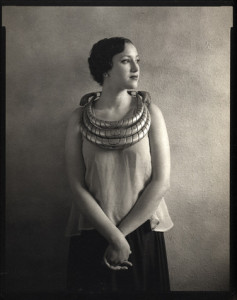

Ray Bidegain is an artist and an educator. He is an accomplished platinum printer whose work has been collected internationally for two decades. He lives with his wife Kathleen and their two daughters, Abigail and Emogene in St. Johns, right around the corner from Jake. Jake’s colleague Sarah Taft also joins the fray.

Ray Bidegain is an artist and an educator. He is an accomplished platinum printer whose work has been collected internationally for two decades. He lives with his wife Kathleen and their two daughters, Abigail and Emogene in St. Johns, right around the corner from Jake. Jake’s colleague Sarah Taft also joins the fray.

Who: Ray Bidegain, Jake, and Sarah Taft

Where: Around Jake’s fireplace

When: February, 2014

What: Bulleit 10 year (which was a gift)

Jake: Well, Ray, you want to start with business or art?

Ray: Or the business of art?

JS: I want to talk about a lot of different stuff – art, business, showing, the museum – where would you like to start? You want to get going with the softball stuff?

RB: Oh, yeah, let’s get started with something easy. You want to go right to the Photo Council?

JS: Well, no. I changed my mind. I want to start with the lifestyle stuff. I want to start by saying: “Ray, you’re my hero.”

RB: Oh, that’s nice.

JS: And the reason that you’re my hero is because you print every day. I remember that you spoke about it during your museum speech – that you work in the darkroom every single day. And that’s what I’m talking about – that’s why you’re my hero – because it’s not a hobby, it’s a full-on lifestyle. So, let’s talk about that.

RB: So, I spend my time between being the primary caregiver for my children and making my work. And this means photographing sometimes, and processing film sometimes and it does include printing every day. I often have prints on order, so I have prints to make for people who are collecting them. And on days when I don’t have anything new to print, and I don’t have any orders to fill, then those are the days when I go back through old negatives which I may have previously ignored.

JS: So, how much of your time is old stuff and how much is new stuff?

RB: Let’s see. For about four months after my birthday, I’m printing orders from my big sale. Any time I have a new negative that I’m excited about, I always find the time to squeeze it in. I guess it’s not really too often any more that I’m digging back very far. Part of this has taught me that I don’t always process film and print negatives right away. I think they need to sort of ripen.

JS: So, are you running out of old negatives? I mean, if you print every day, how long before you have exhausted the catalogue of old work?

RB: Well, when I’m working, I only make about ten prints a day. I don’t make that many because I’m a platinum printer. It takes a while.

JS: You do understand that that’s a lot, right? I mean, five to ten prints a day, particularly in platinum is a lot of printing.

RB: I guess it could seem like it. It’s a matter of perspective. In regards to old negatives, let’s just say that I’m not going to run out.

JS: Really? So, how often do you shoot these days?

RB: Well, that goes in cycles. Sometimes I’ll get frustrated and go out and shoot several times a month. Sometimes I go months on end without shooting at all. I tend to run into the same old difficulties that all the landscape photographers do. And when I run into that, then I switch back and start photographing people again.

JS: Are you doing commission work or are you really just shooting for yourself?

RB: I almost never do commission work. I’ve only done one commission work this year; they always leave me wishing I had done something else. There was a time when I did nothing but commissions, but that ended about fifteen years ago.

JS: Well, that’s been a long time that you’ve making art for art’s sake.

RB: It has. Since I turned forty, really.

JS: You’re not fifty five.

RB: Fifty four. Almost fifteen years ago, and I decided that it was time that I started making pictures that I wanted to see on my own wall.

JS: And how’s that going?

RB: Sometimes good and sometimes…. Well, sometimes I spend a lot of time wondering what it all means. What we’re all facing now, especially, is that even though I spend a lot of time interacting with collectors and making prints, it’s still just not enough. The opportunities are not what they once were. Chances for exhibitions are fewer, the exhibitions are smaller, and the internet just doesn’t do it for me.

JS: Would you like to define “enough”?

RB: I struggle to know if this is because I was a commercial photographer for so long. These days, everything I do is for me, but I still need an interaction with an audience in order to understand my own work. Without that, it’s not enough.

JS: OK, don’t let me lose the thread about your birthday sale. Let’s speak a bit about that, but let’s do it last in process. Will you please describe your process all the way through to selling? Let’s start with the camera – what do you shoot?

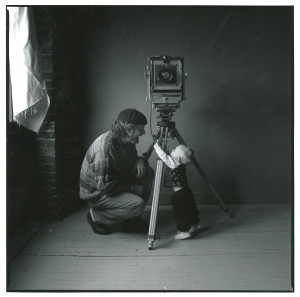

RB: So, I shoot a Calumet 8×10 and these days I have a 4×5 Ebony camera. I am a person who has had a lot of different cameras, but I always have those two formats.

JS: So, you’re all sheet?

RB: I shoot all sheet. Well, now I do. I’ve shot a lot of roll film of course, but now I’m all sheet. I often have an internal struggle about print size. I love small prints, I love small 4×5 prints, but sometimes I need the bigger image.

JS: So, you’re always contact printing?

RB: I always contact print. I haven’t used my enlarger in ten years. This has a lot to do with the platinum – I can do a lot of different alternate processes, but my primary medium is platinum printing, so yes, contact printing. I’m capable of making an enlarged digital negative, but I just don’t think that there’s much love in a digital negative. I mean, they look fine. But they don’t look the same. I’m spoiled, I guess, by the look of a contact print from a film negative.

Ultimately, I’m spoiled by objects. The object is super important to me. It’s the texture of the paper, it’s the color of the paper – all of that beauty tied up into one is what means everything to me. A lot of people say that it’s the image that counts, but for me it’s the object which counts. The object is everything. And how the object gets made is everything to me, too.

JS: Well, I disagree. And I think you disagree, too. Certainly the image counts.

RB: It does, it does. Nobody is interested in an uninteresting image, no matter how nice the execution. The image is of critical importance. But for me, the object counts as much. I’m not happy with it on the internet.

JS: But that’s now how everyone looks at photography.

RB: Right, and that’s a big part of my current dilemma. I’m not sure what that means. The audience is hundreds of times bigger than it is in real life.

JS: And how big is your internet audience?

RB: I’m not sure I really know. Well, I’ve had five hundred thousand page views on Flickr.

JS: And how big is your human audience?

RB: I have about 150 steady collectors. I have no idea how many people came to my last exhibition. My last exhibition was in 2012 and I don’t have one coming up in the foreseeable future.

JS: That was Newspace? That seems like a long time ago.

RB: And I have no idea how many people saw it. I mean, you never really know that.

JS: Well, it seems the internet is a boon in its own way, just in terms of exposure. Is it making you money? Are you selling?

RB: Well, yeah. I sell a lot over the internet.

JS: OK, hang on. We’re running far afield, and I don’t want to lose track of the process conversation. So, you have your cameras, and you’re making platinum contact prints and then what? You want to put stuff on the internet? You want to put stuff in a gallery? You want to do… both?

RB: I used to feel that my goal was to have a gallery show. But they’re difficult arrangements. They’re expensive and hard to procure and so, currently, I get images up on Flickr and my website pretty quickly, but I still strive to get them into somebody’s hands. One of the important things for me is seeing my work up on people’s walls.

I got an email from a person in Japan with a jpeg attached – a simple photo of this person’s hallway, and hanging in that hallway is a little 4×5 platinum print of mine. And the thing that’s exciting for me about that, is not only that it’s so far away, but that it’s up, that it’s a part of this person’s daily life.

I do get emails and letters from people mentioning that my work is up in their homes. And for me, that’s worth much more than the money that they paid for it. I mean, I need the money to live, and that’s important, too – but having them up in people’s homes, to me, well that’s exciting. That’s kind of forever. It’s a little like having your pictures at the art museum. Cause that’s forever for sure.

JS: Let’s go there. You recently sold some more work to the museum.

RB: Yes, after the 2012 Newspace show, Julia Dolan suggested that she’d like to have some of them for the collection. She selected eight prints and I found some patrons to buy them and donate them in their own names, and so now I feel like I have a legacy at the Portland Art Museum.

JS: And you do. Eight prints is a lot. Dr. Dolan says that a good representation, especially for a living, local photographer is three. And you have eight.

RB: Plus, I already had one, so that’s nine. And you know, similar to the photo from the person in Japan, that’s what really helps me go on making work. Making more and more work. It feels really good, and I’m a feeling-driven guy.

Sarah: Because this is something that you created for yourself, but which many other people can also enjoy.

RB: Right. And this was the point of shifting over from being a commercial photographer. I feel like people who work on commission should get paid the most, because it’s the least rewarding in some ways. What’s the most rewarding is to make photographs of your own choosing and have those go out and be enjoyed in the world. And so I’m very grateful and feel very lucky to have anything at all in the museum collection, much less nine.

JS: And let’s stick with the museum a minute. Now you’re the president of the Photo Council.

RB: Yes, OK, that started five years ago when I became president of the Portland Photographers’ Forum board – this is a group of photographers in Portland that has been gathering for thirty years or so to share their own work and to hear photographers speak and so forth. And five years ago, when I became the president of PPF, I was also part of the museum Photo Council with some small notion of joining that board. I figured that the PPF experience would be a good way to see if I could be of some more use to the Photo Council.

The Photo Council has been an exciting time for me. It’s a good way to learn about, and become more compassionate about, the way that museums work. I think that previously I had the belief that a lot of people have – that because of what it costs to go to the museum, the museum had plenty of money and resources to do whatever they please. But the truth is that it doesn’t really work that way, and there is a large and diverse and necessary group of people required to keep expanding the collections.

JS: So, here’s your chance for a full-on Photo Council pitch, Mr. President.

RB: I joined the board of the Photo Council because I feel compelled to help the museum raise funds for acquisitions. And I think this is the whole point – it’s super important that the museum continues to grow its collection. And I think, from an educational perspective, any photographer interested in a better understanding of not only their own work but also the history of photography would do well to join up and see what we’re up to.

JS: I like it because it gets you close to the art.

RB: And that, too. You get to go, through membership, and you get to attend private tours of the exhibitions with Dr. Dolan, and I guarantee that if you do that, you will learn something that you did not know before. About the art on display, and about photography in general – it becomes more interesting, and more in context. The history of photography is much more complex than most people think.

So, it’s a hundred dollars a year. You get to attend a handful of activities and events, and you get a great behind the scenes tour of the photography exhibitions. We have one hundred and twenty members, and we have a good time.

JS: And we get to vote.

RB: Right. Every year, we do a meeting where we help decide which prints come into the collection. Julia brings in her selections, and members have input about how the funds are spent. Ultimately, it helps for a deeper understanding. Of the work, of the history, and of the curatorial process.

JS: OK, I don’t want to lose track of the birthday sales. That’s been very important for you.

RB: Yes. So, when I turned fifty, I used my website to host a one day sale of my images where every image in my catalog was fifty dollars. I sent out a notice to my mailing list. And the first year, I sold about a hundred. And it was excellent, because it meant that I had a chunk of money that I wouldn’t usually have and also, I had a job. For the next couple of months, I made prints and mailed them out. My clients received prints that they didn’t have before, and I had money to live on. So that became a regular thing, and every year it’s gone better and better, and this last year, when I turned fifty four, I sold two hundred and one pictures for fifty four dollars each.

For me, this is how I like to market. I like having my pictures out in the world. The money is nice, but now, really, I have two hundred pictures spread out over 125 people from my birthday sales. A lot of these people are other photographers who were not art collectors. But now they are. They have the experience of what it’s like to buy someone else’s work and own it.

I had this experience in Seattle – a gallerist named Marita Holdaway at the Benham gallery said this: anyone who wants to sell art should make a point of getting out and buying art. So that they know how it feels.

From that day forward, I have always made a point of buying pictures. It’s an interesting feeling and maybe not what you expect. But if you want to sell, you should also want to buy. It’s a discretionary thing – it’s not like buying a car or something – I mean, you don’t have to do it, but what better thing to buy than original artwork? I mean, what else are you going to spend your money on? Posters? There is a lot of great original artwork out there at affordable prices.

JS: And who wants posters? Especially in Portland. There is so much art out there.

RB: And a lot of it is so affordable.

JS: Good segue. Let’s talk about pricing. How do you view the current fine art photographic market?

RB: I think that most emerging photographers price themselves completely out of the market. I took a different route and would always prefer to sell more prints for less money, rather then pursue big edition schemes that would never be realised. First, I want my artwork to be affordable, but also, I want to sell it. I want to be making and selling prints. I don’t want to be sitting around waiting for one to sell. And I always figured that I could sell them at a price where I would be busy, and if it ever got so that one day I was too busy to keep up, well then they would cost more.

And I think that if more artists would treat their career as a job, they would be more successful. Compare it to what people will pay you to make art – there’s no way you can make as much money printing for other people as what you can make in your own basement, drinking coffee and listening to music, maybe or maybe not dressed, making your own pictures for sale. And I get to go down every morning and make prints from my own negatives that I really like. If I was working a job, and a good job, where I could make a couple hundred dollars a day, that’s what I compare that to making my own. If I make ten a day, then I just have to sell them for twenty dollars each, and I’m breaking even.

And I’m not advocating selling art for twenty dollars; I’m just pointing out that selling pictures on my birthday for fifty dollars a piece is not hurting me.

So I’m making all this work, and I’m trying to get it out there, and this leads to showing. This has something to do with you, Jake, come to think of it. I approached Chris Bennett about us having a joint exhibition.

JS: I can’t believe you’re bringing this up.

RB: Well, I feel bad about it, but there’s a point. I approached Chris about us having a two-man show and he said – “Well, how about just you?” and I took it and had a large exhibition.

JS: Because you and Chris Bennett both hate me.

RB: No, no, no. My point is that being able to print every day means I have a lot of work, which led to the Newspace show which led to sales and eventually to the museum collection.

JS: And that was our second attempt at a two-man show. I don’t want to lose track of that, but for now I want to keep talking about pricing.

RB: I try to think of selling art as any other retail business would. Which means that if you’re hanging your pictures on the wall for $400 and they’re not selling, then think of yourself as Macy’s and start to mark it down.

I take a lot of heat for this.

JS: I do, too. “Why are you selling everything so cheap, Jake?” To which I respond: “Oh yeah, well, how many do you want?”

RB: Right. Right. Exactly. They say “Well, you don’t value your own work.” and I think well, that’s not true at all. I value it plenty. I’m just trying to be realistic. If you’re talking about someone who prices their stuff really high, then you’re probably talking about someone who doesn’t need the money from selling. And I do.

JS: Or, there’s an alternate school of thought with selling much fewer pieces at much higher prices, and keeping the perceived value very high. But I agree with you here, because the guy holding out for one at a thousand dollars instead of selling ten for one hundred dollars does not have the ten pictures out there in the world, flying free.

RB: My other feeling about that is that the beauty of me starting out selling my pictures on eBay for not that much money meant that I learned how to make a lot of pictures. It’s a lot of work, and it takes a lot of practice to be good at it. But it’s still photography.

I remember one year getting ready for a show and being buried with the amount of prints that I had to make. I was really busy in the darkroom and was working a lot and thinking about how hard it was and wondering if I was going to be able to keep up. It was summertime, and my neighbor was having their roof redone. So it was good check – I’m looking at those guys up working on the roof in summertime and thinking “Now, that is hard work. And what I’m doing is what I love to do.”

When I first started on eBay, I sold ten, maybe fifteen pictures a week, and I learned that I could get fifteen pictures out the door every single week. So if anybody needed fifty prints for an edition in a month, I could do that, and it wouldn’t have to hurt. I hear about others, they need a year to get ready for something like that.

This helps me cycle through my work and learn how to do it. It’s kind of like golf. It’s practice.

JS: Let’s talk about eBay. Are you still selling stuff on eBay?

RB: No. Not for a while.

JS: And when did you start and when did you stop?

RB: I turned forty in 1999 and started the eBay thing. Ebay was new at the time, and the way that I did was I said: OK, I have a two-year old baby that I’m in charge of, and that’s that. Now, how much do I feel like I need to contribute to the household in order to feel good about my part-time job as a photographer? And it was two thousand dollars a month. And then I said, OK, so if I work on this while the baby’s asleep, then how many pictures can I make in a day? I came up with forty a month – ten a week, and what I need is to make two thousand dollars. So I put them on eBay for fifty bucks each. And I sold six hundred of them the first year.

For me, that’s thinking about it as a business.

JS: Jesus – OK, so you made thirty thousand dollars on eBay in your first year.

RB: I did. It worked out.

JS: Six hundred prints in a year is staggering to me. I mean, I’ve been at it nowhere near as long, but I haven’t sold anywhere near that in the six years I’ve been actively selling. And this was your first year, and this was twenty years ago. It’s staggering.

RB: Seventeen years ago. At that time, eBay was new, and it cost like $1.50 to market, and it was easy. My whole plan progressed like this – I did eBay for about four years and I gained about one hundred and fifty solid collectors. And then I quit eBay and started marketing directly to those same collectors. I have individual collectors who have over one hundred prints each. I mean, I’m not bragging – it’s just work.

I asked one of my collectors in Texas and said “What are you doing with all these pictures?” and he said: “I’m waiting for you to get famous.”

So, he’s got two things: he’s buying them aesthetically, and he’s also – truthfully – he’s also speculating. And I don’t feel like I have to deliver on that. I mean, I have to deliver on the aesthetic side and so he got a good deal either way. But if I do get famous, then good for him.

JS: All you need is a good hostage situation and maybe a heroin overdose, and he’ll be rich.

RB: Yeah, OK. I’ll keep that in mind.

JS: So, what sold on eBay?

RB: Nudes.

JS: Right. Let’s talk about naked lady pictures.

RB: Truthfully, when I left commercial wedding and portrait photography, I had taken landscape photos equaling zero. I never thought I was going to be a landscape photographer. And it didn’t take long to figure out that people don’t very readily buy portraits of people they don’t know.

JS: Amen.

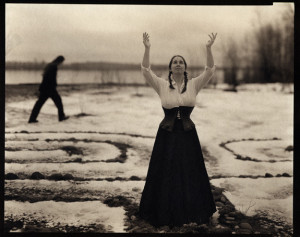

RB: People will buy pictures of people they don’t know fairly readily, if the people in the pictures are not dressed. Hmmm. Also, I feel confident that my work has never been as exploitative as that just sounded.

JS: And how do you make sure that your naked lady pictures are not exploitative?

RB: I feel like they are anonymous and that the power lies within the subject rather than the viewer. I just had a long discussion with a friend about this. It’s never that these people are just available, or available at all. Part of it is because I want the subjects to be universal, and part of it is from my real emotions. Part of it is from what it’s like to have a two-year old daughter.

JS: Yeah. You live in an all-girl house.

RB: Right. And when you’re a dad, you have to work for it. Mothers immediately have a relationship with their children; dads have to work for it. I’ve always wanted to be the kind of dad with a deep relationship with my children. And when they’re young, it’s a busy time.

Listen, when the kids are one or two years old, it’s a lot of work. This is why so many couples get divorced during this time – you’re so focused on just getting this kid going that you sort of lose track of each other. And so a lot of what that early work was about, for me, was that whole feeling that my wife, my partner, this woman in my life, was not as available as she had previously been.

And so I wanted the models in these photographs to also be unavailable. Does that make sense?

Sarah: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

RB: And so I really tried to carry that across. These are all voluptuous nude women, but they are not, in any way, available to the viewer.

And so now, I still make those kinds of photographs – far fewer but I still make them. These days, the interesting thing for me is that everything has changed again about that whole genre of photography.

Because of the internet, I feel like most of the nudes that you see now are more about having the identity intact, and it’s just somebody in a picture who happens to be undressed. But I’m still striving for the anonymity, and this power thing – I want the models to represent all women, and not just the individual person. It’s not easy.

I was really pleased that one of them got chosen for the museum.

JS: What else was chosen?

RB: Well the sticks, you know.

JS: Oh, I loved the sticks.

RB: Yeah, me, too, and Julia said it was her favorite. But otherwise, they didn’t get a lot of attention. This take me back to something I read in interviews that always bugs me: “My wife is my best critic.” My wife is very supportive, but she is not my best critic.

JS: So Kathleen didn’t like the sticks?

RB: No, Kathleen did not like the sticks. She thought it was boring. I wouldn’t say she’s my worst critic – Kathleen is my “everyday viewer” critic – she feels like she’s the voice of everyone when looking at my work. But my point about the sticks is that she’s not always right. And she’s often quite critical about pictures that I’m quite fond of. But I learned long ago to stick with them.

Sarah: They look like bones.

RB: That’s the beauty of them. They do look like bones. And it’s good. I like the nudes, but it’s my goal that they won’t be my main work. And I’m happy that on my last birthday sale, more than half the pictures were non-nudes.

JS: And what about on your fiftieth birthday?

RB: Way more. Mostly nudes. The shift is nice. So that’s the thing – in a gallery setting, I sell landscapes and still lifes and on the internet, I sell nudes.

JS: Well, that’s informative.

RB: It is informative. I had a chance to have my portfolio reviewed by the late Terry Toedtemeier, and I showed him a variety of landscapes and nudes and some still lifes and his comment was, pointing at the nudes: “There is no shortage of collectors for these photos.” This didn’t make me feel better or worse – it just was what it was.

I got off this topic before, but making nudes was a natural move for me when I stopped being a commercial photographer. No one would buy the other portraits, but they would buy the nudes. And at that time, I really felt that I needed a person to interact with. I had to teach myself to do landscape photography.

JS: So you had to shoot nudes in order to make portraits and have something to sell.

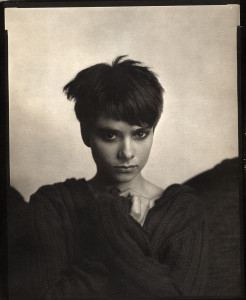

RB: Yeah, to be able to take pictures at all. It was clear that I didn’t want to take commissions. I mean, I know you take portraits, but I think they transcend in a very different way.

JS: Plus, I’m not trying to make my living on it.

RB: Your pictures tell more about the people and more effectively than mine do. Because of the setting.

JS: I’m aiming for the opposite of anonymity.

RB: You are, clearly. But the other thing is, like you said in your talk, you have the collaboration going, where they show up and they have their own agenda. Just like you said – whose picture is it? I find that highly interesting.

They bring a bigger piece of themselves. For the sake of comparison, I’m using models, and you’re using individuals.

JS: And they’re deciding what they’re going to put in front of the camera. It succeeds or not based on that, or on my ability to modify the situation.

RB: Or at least let it unfold. And you already have people knocking you off.

JS: Hmmm. It’s interesting to be a young photographer who people are already claiming to be “knocking off”.

Sarah: I knock him off the best. Wait, that came out wrong.

RB: And that went right on the tape. The only people who are stealing my bit are students, which I think is always amusing – but I perpetuate it because the ones I like the best are the ones that look just like mine.

JS: OK, let’s talk about people stealing each others’ bit a little. Now, you make naked lady pictures, and how do you do that without making one that I’ve seen a hundred times before?

RB: I’m not sure that I am. I’m not convinced I’m giving anybody anything that they haven’t seen before, and that is not my major goal. I feel like photography has suffered at the hands of young photographers who feel like they always need to do something that no one else has done. I feel like we have a lot of ugly pictures as a result of that.

That being said, what I feel like I’m giving you is a sense of calm, organised beauty. Regardless of my subject matter, whether it’s a landscape or a building or a still life, I want a calm sense of beauty. I don’t want it to be titillating if it’s a nude, I don’t want the sky to look like Bolivia, I just want it to look like something which you can look at and say ‘I feel better’.

It’s not something you’ve never seen before, but that’s not the point. It’s mine. I mean, I’m not shooting “Pepper 30” over – I’m not going to do that but I am making traditional prints of traditional subjects and sometimes struggle with feeling completely irrelevant in the modern world, but I don’t care. The whole idea of being an artist instead of a commissioned photographer is that you do what you feel like.

JS: So, talk about content in regards to traditional vs non traditional imagery.

RB: Well, if I were to put my finger on the pulse of what’s popular in galleries today, then it would be much more social documentary-driven. In fact, you can read prospectuses for group shows, and that’s what they want. For me, NPR handles that. We’re not in charge of that.

JS: OK, so what are you in charge of?

RB: I’m in charge of soothing everybody. Making people feel good. It’s kind of a generational thing – I’m way too considerate to show you something that’s going to piss you off.

Sarah: That’s a whole other thing. There’s a whole other generation which can do that right now.

RB: Right. Not my department. And then, even since then, since the social documentarians, there has been a whole new generation. I mean, Abigail’s in high school, and she is so thoughtful and optimistic and global. She doesn’t just want everybody to be happy, she wants everybody to succeed. And it’s so genuine, it makes me really happy.

JS: So someone, presumably from this middle generation between you and Abigail, once described “good” art as that which does not match your couch. And their point was that they want the art to challenge you, they have the need for the aggressive documentary style – if it’s not making you uncomfortable, then it’s not fulfilling the purpose of art. Your point is much the opposite, that art can, and should, look good over the couch.

RB: Exactly. I mean, what do you think? What do you want over your couch?

JS: Well, you know that I want the soothing and organised beauty. Only beauty will save the world.

RB: Yeah, this is cause we’re romantics, I think. I don’t want to soap box too much, but when I see modern portraiture, I see people taking banal pictures of banal people and I think to myself, when these people modeled for these photos, they had no idea what they were getting into. They didn’t realise that these were going to be 8×10 color photos of them looking extremely plain or boring or banal. And I don’t think that’s OK.

JS: Well, it’s the difference between taking pictures and making portraits, if you ask me.

RB: I think so. And I also think it’s too easy. It’s too easy to point out how things look bad.

JS: We talked some about exploitation in the nude, but I think it pervades a lot of “dressed” portraiture, too. It always drives me crazy, and always drives me off. Some photographs only look, to me, like the subjects are being taken advantage of.

RB: They look like angst-ridden teenagers, or disheveled grown-ups who don’t have any money or whatever.

JS: And lots of even maybe well-meaning documentary work, like the ubiquitous shot of the poor girl in Afghanistan – here, let me take your picture and get famous off that. I know there’s a flip side to this argument but…

RB: But, guess what? Everybody already knows it’s bad. And I’m not interested. But I’m going to stick with it, even if it doesn’t work out for me. There are several things I’ve done in my career that mean I’m not having a big show in a fancy gallery, but I’m happy with the things I do. And I’m getting the work out.

JS: We’ll get to galleries in a bit. First, let’s talk about the future of photography.

RB: For me?

JS: Sure, let’s start there.

RB: I worry about doing the same old thing. But I really am not compelled to do anything else. I just want to keep making the same genre of pictures that I’ve always done. That’s what turns me on.

Every time I do something wildly, dramatically different, it never makes it to the print.

Sarah: What about side projects?

RB: I try, but I never like it. I don’t know if this is me being weak or me being fixated, but it just doesn’t feel right. I talked to Jake about this a few weeks ago and said “Jake, do you ever think about making a different kind of picture?” And Jake comes back with “I’m thinking about making a horizontal one.” And I love that. It’s exactly how I feel.

The mantra I constantly hear is “You have to do something new”, and I’m a little fed up with it. I had someone that I respect recently tell me that I’m too much of a craftsman and not enough of an artist.

JS: What does that mean?

RB: He felt like I need to take pictures I’ve never taken before. But I was a little pissed. I think craft is super important but I don’t feel like my pictures are strictly about craft.

JS: But we’ve already discussed the importance of the object. And I think you implied that it’s ultimately more important than the image.

RB: Well, that’s not true.

JS: OK, so let me ask you really explicitly – would you rather see a really banal image which was incredibly well executed, or a compelling image on an iPhone?

RB: That’s not a fair question.

JS: It’s a mental exercise. And you only get to choose one.

RB: I would say that I would be equally disinterested in both of the modes. What I really want, obviously, is both at the same time. I don’t think a photo on an iPhone is a photo. And the perfectly executed boring photo is just that – it’s boring. I want both. I want it all.

JS: Well, you’re dodging my question, but I’m not surprised. I think the answer comes down the same way for everyone, eventually.

RB: Obviously, the picture has to be good, I just think of the iPhone photo as a “vernacular” photo, which can be really beautiful. But it’s different than the “intentional” photo.

JS: Maybe we should have a symposium on different terms to reflect the different kinds of image making. I’m feeling less and less like what I’m doing is even “photography”. At least not in its new definition.

RB: Right. The phones are fun, and they change everything. I was laying on my bed, and I took a picture of my ceiling fan, I added an instagram filter, and thirty seconds later, twenty two people liked it. I mean, that’s a huge shift. But honestly, I was just bored. And I don’t think art comes from people being bored.

JS: I’m remembering this great thing you said about phone photography one day while we were out walking.

RB: What? I don’t remember.

JS : You’re lucky I was paying attention. I quote you on this all the time. “Phone photography is to real photography what phone sex is to real sex. It’s fine if you don’t have any other options. But hopefully you have other options.”

RB: Yeah, that sounds like something I’d say. Phone photography is cool, but there’s a difference between cool and beautiful.

JS: They can’t be both?

RB: Jake, I feel like we’re spinning in circles.

JS: In fact. OK, so let’s move on to galleries. We’ve been talking about this interview for a year and a half, and one of the first things that made me want to do it originally was your phrase about artists: “We need to get our balls back.”

RB: Right.

JS: So, you want to talk about galleries? You want to burn some bridges?

RB: Well, at that time I had just started thinking about how photographers got to the point where we would be grateful, after a long process of work, that we would be selected to spend two or three thousand dollars of our money to put our pictures up in someone else’s business, where the business is specifically to sell work, and have the expectation that we would then take them all home.

So many of the photographers that I meet say that they have shows, but that they don’t expect to sell anything. I don’t know what other person would get to the point where they thought that was a good idea. I mean how did we lose track of the fact that galleries need us more than we need them?

Look at it this way, here’s this business whose point is to have twelve months of programming, and we are supplying all the work. If it’s two thousand a show, then that’s twenty four thousand a year worth of material which isn’t even on the gallery’s budget. So, without us, there would be no gallery, but we have taken the back seat to where we feel lucky to have a show and don’t have any expectations of making any money from it. And the split is 50/50, but all the production costs come out of our side.

I had a perfect experience once, where a gallery requested forty of my images and I sent them the forty loose prints – they matted them, they framed them, they advertised them, they sold them, and then they paid me. It was beautiful. But that’s not the rule.

So, for instance, I feel like the split shouldn’t even happen until costs have been covered.

Galleries, in their defense, are trying to make money, too. And I know that they have a lot of expenses. Big, established galleries, with big name artists, have a good chance to make money. Smaller galleries, with emerging artists, well, just the sales can’t make it. Which takes us to juried exhibitions. Now you’re spending an additional thirty dollars for the privilege of hanging your picture on the wall. And there are so many of us.

JS: But that’s the whole issue. I mean, for every gallery, there’s twenty or thirty artists lined up out front.

RB: Twenty or thirty? Forget about it. There’s a hundred.

JS: That’s my point. Sure, galleries need us to have a point, but we also need them. Like we’ve both said earlier about needing an audience to finish the work, and we can’t do that without a gallery willing to take on the risk and the overhead and the associated work.

RB: But it’s not working out. There used to be a small number of gatekeepers, and if you didn’t get the nod, you didn’t make it. Now, everyone just goes to the internet. Now, we all establish our own resume. I don’t know what the answer is.

I know a lot of photographers who feel that the gallery system is so damaged that they just go right to Flickr, and that’s where they get their audience participation. It’s enough for them – they don’t need to capitalise on it financially, they capitalise on it emotionally. And that’s all right, too.

But I don’t like the change in the business model – while we were busy thinking it was OK to pay and mount pictures that didn’t sell, galleries lost track of their job – creating a stable of collectors which they could rely on to come and collect the work. And juried shows are a different way of doing it, and that’s what’s happened – the artist has become the target market for the gallery, instead of the collector.

JS: Yeah, but you’re still not fixing it. What do you suggest to gallery owners?

RB: Not my job. My job is making the art.

JS: Well then, you shouldn’t bitch. Let’s pretend that the world righted itself in your eyes – what does it look like?

RB: It looks like this – the gallery is now an approachable venue with affordable art on the wall. This is how stuff sells – you and I both do this – it’s good to sell stuff for one hundred apiece and actually sell stuff. We come away feeling OK, the gallery make some money – everybody makes some money.

So why isn’t this the norm? We see most pictures on gallery walls for four hundred to twelve hundred bucks apiece, in a market which doesn’t sustain it. So we see no red dots.

Guys like us, we have more success selling “cheap” – I sold platinum prints at the Newspace show for $225 apiece and sold nine or ten of them – that’s pretty good. I remember you selling for ninety nine bucks apiece, and having a good night. So it works, but how much heat do we have to take for this?

In the old days, galleries had work up on the wall, and they had a different agenda. They wanted to make sure they sold, and sold a lot. And I feel like that’s changed – at that time, no one entered into the transaction thinking they weren’t going to make any money.

JS: And now we do.

RB: It’s all pay to play. The gallery business: if you want your pictures on the wall, you have to pay to get them there. The road to getting your work out consists of things like Photo Lucida, portfolio reviews, etc. It costs a lot of money to be an artist, these days.

JS: Are you going to float the idea that when you were starting out and twenty years old that the field was less crowded, or somehow different?

RB: I was different – my goals were different. I was a wedding photographer when I was seventeen years old. I went to commercial photography school and I wanted to be Richard Avedon more than I wanted to be Edward Weston. Meaning, I wanted to be in the business of photography.

I don’t know when it was, but it was much later that I realised that I wanted to make my own work. And I don’t know that there were that much fewer people making art. Or that there were more venues. It’s less about us and more about galleries not being properly managed.

JS: Ever run a gallery?

RB: No, why would you? I mean, there’s no money in it. If you had a guy like you or me in there every month, and we sold some things, but they were cheap, then what would happen?

JS: You could scrape by.

RB: Right. And you’re not going to get rich off of it. Maybe the issue is that people going into the gallery business are the same as the artists – they have high minded ideas about how much money they’ll make. I mean, how does that compare to the camera store business?

JS: I see your point. It lends itself to this evolving theory I have about why people get into business, and who gets into business. First, you’ve got people who are really good at something, and they really love it and they want to share, it’s all they want to do. Or the other people, who have a really good idea – an idea so good that it’s liable to make a lot of money.

So, you’re walking down the street, and it’s time to buy a hamburger. There’s Joe’s Hamburgers – it’s right there, and Joe is a hamburger savant – he’s dedicated his whole life to it and it’s what he’s really, really good at. Then there’s McDonald’s right next door. There’s no one in there who’s dedicated their life to the hamburger, but they have a really good model for the production and distribution of hamburgers. It’s very efficient.

And the McDonald’s is always going to work better, because people are, by nature, conservative, and they want to know what they’re going to get. Walking into McDonald’s, they know exactly what they’re going to get, every single time. Yes, there are people who will, for one reason or the other, deflect to Joe’s, but it’s never going to run as efficiently. The passion will never outstrip the efficiency.

RB: Are there are enough people who are not that conservative so that it could work out?

JS: That remains to be seen. Furthermore, we live in this bubble – we live in freaking Portland, and the rest of the country is simply not like this. The idea of small business or shopping local still seems, to many Americans, to be some sort of vaguely leftist plot. Here, maybe Joe’s hamburgers could get some traction. Anywhere else, forget about it.

RB: So, let’s apply this to a photo gallery. Say to yourself, what if Joe Gallery committed to beautiful, affordable artwork? And every month, he brought in another guy that was making work which Joe’s clients could relate to and could afford. People would start to go there, because they would rely on that gallerist to help them.

This would be different than the more mercenary approach – the thinly veiled efforts at making money through group shows. In the case of the group show, the gallery makes money, but what does the viewer get? He gets, she gets, disjointed groups of not particularly well-realised work. The photographers who are doing well, the committed people, they’re not participating in group shows. I’m not saying that there’s no good work in group shows – but a lot of it is people who aren’t the full-timers.

This model that we’re talking about here – emerging, accessible, and affordable, well that could work.

We need to stop complaining about how Portland doesn’t want to buy artwork which doesn’t cost much money. Guess what? Here’s where we live. If we don’t like it, we should move. I sell what I can to the market which I have available to me.

Look, art and commerce is a bitch. There’s no doubt about it. I’m sympathetic to the gallerists out there, and I know it’s hard. But my point is that we, as photographers, somewhere along the line, lost our nerve. It wasn’t about how much we charge. It’s about what our value is. Not dollars and cents, but the value of the objects that we’re making. This is why now we see inkjet prints stuck on the wall with magnets.

I’d love to see galleries buying frames – write a grant and get a set of gallery frames in three sizes, so that when Ray, or Jake, or Sarah gets a show, we’re not burdened with the expense of putting up work.

JS: Which sounds like a scheme for helping what you’re calling the “broken” gallery system. Probably about time to address issues on the artist side, as well.

RB: It’s all the same problem, really – a lack of realism. The bulk of living photographers want prices like they’re dead. I had ten pictures in the drawers at Blue Sky – priced like usual at $225, and I sold seven of them. I felt pretty good about that. Everybody else was way more. And when I say I sold seven, people ask how much and I tell them and they say “Oh, well that’s why.” But the pictures sold. And now I have seven more out in the world, and a thousand dollars to show for it.

How much do you make working a regular job? How many jobs can I get where I can work from 9-3 every day, nine months a year, have the summers off, and be able to take care of the kids when they’re sick? For me, that flexibility is everything. It’s a funny equation, and it ends with me making art.

I don’t think I’m alone in saying that the gallery system is broken. For most of us. There is a small percentage of the galleries and artists that work very well, and make tons of money. Julia just came back from Paris Photo and clearly lots of pictures got sold there. And I always felt like if that’s going to happen to me, then the best way is for me to arrange that is to do what I’m doing now. Because if I don’t get a lot of pictures out there, then how the hell will anyone know who I am?

And if suddenly I become that guy, then I’m ready. I can’t force it, but I can prepare for it.

JS: Yes. Putting your time in in the trenches, over the course of the last twenty years, and working it: selling on eBay, selling to collectors, and working every day. The birthday sales, all of it, it all accumulates. I’m proud of you because you’re not expecting to make a photograph and suddenly become a rock star. You’re working for a living.

RB: I am working for a living. And if the other thing happens, then great, but that doesn’t happen very often.

JS: I know. I look around at some of the talent that we have just in Portland – really credentialed, mature talents who are collected internationally and published and exhibit regularly, and ultimately, they’re not super famous and wealthy. Most of them have day jobs. Stu Levy has a day job.

RB: And me, I don’t even have a job. I mean, I work every day, but it never feels like work. I mean, I’m not rich, and I won’t be rich, but then, again, I don’t have a job. And that’s all you can hope for.

JS: In fact. This is when you start calculating your wealth not based on money.

RB: Right. Although my retirement might suck.

JS: Well, there is no retirement. The good news is you’ll be able to be in the darkroom when you’re seventy.

RB: Which sounds great, except I think I’ll have that same existential problem: What’s it all about? That’s what keeps bugging me.

JS: The point of having the interview is for you to tell us.

RB: I think I obsess too much, and ignore the fact that I’m already doing it. My mother had the same advice for me, recently. She said “You spend too much time thinking about it. Just do what you do.”

JS: And that seems like an excellent place to sign off.

RB: Thanks, Jake. Thanks, Sarah.

JS: Thank you. And good night.