Drinking with Jake (Round Four) – Mike Bain

Written by Jake Shivery

Next in a series in which Jake Shivery and a guest get pickled and talk photography.

Mike Bain is the US Marketing and Business Development Manager for Harman Technology / Ilford Photo. He has been with Ilford for 26 years and he has been working in the photo industry for over 35 years. He keeps busy with photography, travel, walking and reading. Mike and his wife live in the beautiful Oak Cliff section of Dallas, Texas.

Who: Mike Bain – Ilford, US Management and Development

Where: Jake’s garage

When: March, 2014

What: Bulleit Rye with a bit of ice

Editor’s note: Please note that this interview was conducted in Two Thousand and Fourteen, and it’s just taken a long time to actually get it into print form. There are a variety of points raised where the time is relevant, so kindly just pretend for a second that we’re back in the salad days of early 2014. Sorry – it’s been kind of a crazy year. js

Jake: Thanks for coming to visit us in Portland.

Mike: It’s my pleasure.

JS: I understand that you enjoy beer, so I figure you might also enjoy Portland.

MB: I do like beer, as it turns out, and I really like Portland.

JS: You find us to be a good town for beer.

MB: Oh yes. I like pale ales especially, and there are many.

JS: Anything in particular?

MB: I have to say, everything I’ve tried here, I’ve really enjoyed. Just last evening, I went to a brewery downtown and had one of their pale ales. Down the street from Powell’s – that was nice.

JS: You travel a lot. You once told me that you’ve spent three weeks a month on the road for most of your career.

MB: Yeah. At least three weeks. I cover the whole country, so I move around a lot. I started about this time in ’88 and at first I just covered the Southeast as their technical rep. I moved to Dallas from Chicago, and I covered Texas, Oklahoma, over to the Carolinas and down to Florida, where I supported our salespeople.

JS: So all the way back to ’88, when it was all darkroom stuff.

MB: Oh yes, all darkroom. Back that far, we weren’t even thinking about digital process yet.

JS: You’ve been at this for a good long time, then. How do you describe your job now?

MB: I do a little of everything. I guess one of the reasons that I’m still around is because I have a bit of a technical background. These days I say that I do everything from talking to someone when they develop a roll of 35mm film to talking with people like you and big labs and then all the inventory – making sure that we have the right products in the United States.

JS: This came up earlier today when you were speaking with the rest of the staff, but what do you need the public to know about Ilford?

MB: I think that the main thing is that despite some of the bad news that people may hear about traditional photography and things like that, we are financially stable and plan on a long future. We continue to develop new products and plan on being here for quite a while. I mean, it can be a challenge, but really, everything about this industry can be a challenge.

JS: It’s interesting to note that Ilford has just released a brand new fibre paper. Just late last year. [ed: again, that’s 2013, folks]

MB: Yeah, actually two brand new ones. We’ve been producing Multigrade IV since ’93 or ’94, and since then we’ve been working on the new stock, which we’re calling Classic. It tones a little nicer than the IV paper, and has a great contrast range, everything you’ve come to expect from the IV, but even better. We’ve also introduced a cool tone version – we’ve never had a cool tone FB material before, so now we have the Warm Tone and the Classic and also the Cool Tone FB papers to offer.

JS: That warm tone paper has been my favorite for the past six or seven years now. It’s all I print on; literally, everything I’ve souped in the last few years has been on that paper. I think it’s the best thing since sliced bread. How old is that paper?

MB: I want to say it’s eighteen or nineteen years old. We haven’t changed anything on that, which will be important to a lot of people – we have a lot of people using that and enjoying it. That paper already tones great – it looks great – we don’t know what we could do to make it much better.

JS: As I say, I think it’s already a perfect paper. Are the new cool tone and classic papers sort of catching up to the warm tone?

MB: Well, they’re very different papers. Anyone using the warm tone paper will notice that it’s much slower – it’s a totally different emulsion. And then the toning – the warm tone paper has a much easier time taking toners.

JS: And how about the Fine Art paper – where does that fit in with the line?

MB: It’s certainly a niche product. We’ve wanted to make it for a while, but we had difficulty finding the substrate that could withstand being in solutions for a long time without falling apart. So Hahnemühle now provides us with that base, and we coat it with a very similar emulsion to what’s on the FB warm tone paper. So if you’ve printed on the warm tone paper, you can easily transfer over the same techniques to printing on the Fine Art material.

JS: I’ve found that to be exactly true. I’ve pulled the same neg on both the warm tone paper and the Fine Art paper and managed to lose track of which was which while they were in the trays. When they dry down, though, they look much, much different.

MB: It’s not quite the same DMAX, and then there’s the surface, but it has a nice look all its own.

JS: I find it to be a great “limited edition” paper, and by that I mean that I like to use it when my focus is just a hair off. The textured surface does a great job of disguising that, while still giving me a beautiful fibre print.

MB: That’s funny, I recently spoke with someone doing the same thing. They were printing their grandparents’ negatives, and wanted fibre paper, but some of the negs weren’t exactly sharp – I suggested that the Fine Art 300 would be a good way to go, and they were happy with the results. We certainly don’t sell as much of it as the other papers – like I say, it’s a niche product – but I like the way it fills out the lineup. People had been asking us for a textured paper for years, and we’re pleased to have an offering. And it has its own following.

JS: Yeah, it’s good stuff. Anything you want to say about RC papers?

MB: Well, the truth is that we’ve certainly seen a decline in RC paper sales from many years ago. We were a much bigger company twenty years ago, of course, but over the last three or four years the market really seems to have stabilized. There is a slight decline in RC paper sales – Fibre is holding its own, and film is good – very stable – we’re selling lots of sheet film – so of all of our products, RC is the one that’s shown the most decline. It’s more or less stable, lately, but darkroom folks really seem to be gravitating to the FB papers.

JS: Right, well, people that are taking the trouble to go in the darkroom at all are skipping over the RC step. It no longer really seems that much “faster”.

MB: Exactly. That’s what we think. People like the unique look of the fibre. I still tell people that fibre is almost always going to be the longest lasting print in the room. And that look, I mean nothing else looks like that. You can put it side by side with even the most beautiful inkjet print, and fibre will still hold its own. There’s just something about the way it looks and the way it feels.

JS: And it’s the only thing which adheres to the HABS criteria for archivability.

MB: Yes, I’ve spoken with several people about that, people who need to fulfill the needs for archives. It’s great that we still have a product which can be tested for such long term stability.

JS: Yeah, we run the lab to HABS criteria – it’s nice that they’ve now done away with the single weight and the graded requirements.

MB: We do still have a limited amount of graded paper in grades two and three that we offer. When I first started you could get all the grades, one through five, in all kinds of sizes. The multigrade material has really taken over since then, though we are continuing to maintain a bit of the graded stocks for folks who need it. It’s a shame to lose any of the materials, but we like to think we have something for just about everybody these days. And we’re putting a lot of emphasis on film stocks, as well.

JS: And you do have a very thorough selection of film available. What’s the most recent film that Ilford has released?

MB: SFX – the extended red film. Use the dark red filters, and you can get infrared-type results without the handling issues that you have with true infrared films. And then, if you shoot it with no filter, it’s also a very pretty general use 200 speed film. That’s nice, since you can mix both results on the same roll of film.

JS: What’s your most popular film these days?

MB: Hands down, HP5+, 35mm, 36 exposures.

JS: In the store, it always seems like we’re selling more 120 and sheet film, but Ilford at large continues to sell more 35mm?

MB: 35 is big, but there’s no question that 120 film and sheet film have really done the best over the last several years, looking at the uptick in sales. I think that there are a lot reasons for that – there are a lot of really great 120 cameras used on the market, for starters. People may have wanted these cameras for a long time, and now the prices are down where they can afford them. And the plastic cameras, the toy cameras – we’ve really benefited from that quite a bit. 35 still defines the student market though – we do very well with the 35 films bundled with the RC paper. I’m pretty fortunate in my job because I get to meet a lot of different photographers and a lot of people doing really interesting work. I meet photojournalists who have to take digital for their work, but they tell me that they still shoot film for themselves. When they’re doing their own projects, they shoot all film – and of course, a lot of those folks are shooting 35.

JS: We hear the same thing, pretty constantly. Digital for work, film for art.

MB: Exactly. It’s funny, when it’s important, the same people want to do it on film.

JS: Do you have any products that you don’t think people know enough about?

MB: Well, we mentioned SFX, and I do feel that it gets underrepresented a little bit. We’d like more people to know about the Fine Art paper – if more people saw it, then I think it would become much more popular. It’s a nice option – it’s good to have prints that can look so very different.

JS: OK, so Ilford recently got out of the color material market altogether, which has been causing quite a bit of gossip. How do you wish to describe this? What went bankrupt and what is still around?

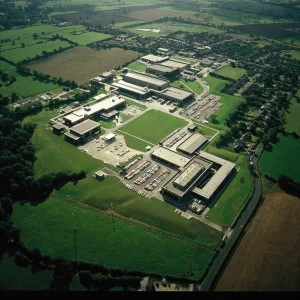

MB: Well, when I got started, there was a company called Ilford Limited. This was an umbrella company for all the worldwide operations – we had manufacturing plants, most importantly in Switzerland and the UK, and at one time also in France. Then there were selling companies, like Ilford US, and Ilford Germany, etc. In the ’90s, as digital really took off, we started making a lot of inkjet products. We were doing it from the beginning and got better and better at it. But the fact is that we were a bit overwhelmed by it and the transition was abrupt and difficult for everybody in the industry. So, we were this big organization, centered in the UK, and we went into some debt trying to make the transition to digital. During receivership they started selling off bits of the company, piece by piece. Right about nine years ago – almost exactly – receivers were handling all of the assets. At that time, the Swiss company was sold off to a Japanese company and my boss, Steven Brierley, along with five of his colleagues, went to the receivers and said they wanted to buy the UK black and white business. At that time, we knew that black and white was still solvent, and it was all of the other interests which were dragging it down. We knew we had a solid business in black and white materials, if it would be allowed to continue. So they bought out the black and white division, and renamed it “Harman Technology”. That’s the legacy name – the guy who started Ilford in the 1870s was named Alfred Harman. We have the Ilford BW brand name for use in perpetuity, but only on black and white products. The company in Switzerland took over all the Ilford color products, including the beautiful Ilfochrome materials. They made this, plus all of the inkjet products, and all the RA-4 color printing products, and the Ilfotrans and so forth. Basically, Switzerland got all the color, and the UK got all of the black and white. Recently, you may have heard news about Ilford Switzerland’s bankruptcy. The Swiss color company has been through some tough times and is now in receivership. This has no impact on us in the UK, since we are separate businesses altogether. That’s what we want people to know. It’s unfortunate about what’s happening in Switzerland, but it’s a separate entity and we’re not affected by it.

JS: So the Ilford Black and White company is stable for the long term?

MB: Oh, yes. I have to say, we run a pretty tight ship. We’re streamlined, and very conservative in our approach. We’re solvent, secure and looking to the future.

JS: You have a very long term lease on the film manufacturing plant.

MB: Yeah, it’s twenty years or something like that. We have the facilities to make everything we need to, plus a lot of room to grow when the need arises. We’re always looking at where a new product might fit in.

JS: So, how about an industry overview from you, as a person, and from you, as the Ilford rep?

MB: Well, obviously, it’s challenging. But when I look around, and I mean, it’s easy in hindsight, but from my point of view, the people who have remained, or become, successful, are the ones who focused on their niche markets. We used to have an industry of people who did a lot of everything, and I think that became part of the problem. The ones who are surviving are the ones who are dedicating themselves one way or the other to smaller segments of the business.There used to be a lot of commercial labs who would order rolls and rolls of paper and the big blue barrels full of chemistry, and most of that business is gone. There is still a little of that work, but there are fewer labs, and the ones who keep going are the ones who really show the dedication to specific services. The art market has always been very important to us, and is even more important now. And education, of course – we still visit as many schools as possible. It’s always very reassuring to me when I visit schools and find that people still think teaching traditional photography is important. The skills make better photographers, ultimately, whether they end up shooting digital or film.

JS: We deal with this all day, every day. It seems like the students want to take darkroom classes, and the teachers want to teach darkroom classes, but there remains this resistance from above – there’s a philosophy among the school boards and the PTAs and so forth that we shouldn’t be teaching this “dead field”. Care to comment?

MB: I’ve seen that, too, and I’ve heard a lot of different things. Sometimes it’s as simple as a school administrator who has gotten their first digital camera and has become a convert. So now the instructors have to do the job of selling to their own administrations. They have to be the ones to throw in on why the darkroom is important, why it matters, why it’s still completely valid. Sometimes, in cities where the rents are high, it’s as simple as the darkroom taking up too much space – I hear that more than you want to know about. But what I do hear consistently is that when there’s a class for traditional darkroom, it fills. I’ve never had an instructor tell me that they can’t fill a darkroom class. That’s very reassuring. Young people find it fascinating – it’s so different from every other aspect of their lives. I always love it when I meet a twenty year old who shows me beautiful silver prints.

JS: This is something we say all the time. Every kid’s got a computer in the kitchen, but nobody has a darkroom at home anymore. I see it as the goal of the school to be providing facilities that aren’t otherwise available, and giving the kids a chance to learn new skills. My shorthand is that we don’t give up all the pianos just because we have computers that can do the same thing. That seems to resonate with a lot of parents and administrators, when I can get them to think about it like that. Furthermore, we’re on the cusp of giving up all the metal shops and wood shops, and replacing them all with 3D printers. I mean, I appreciate the usefulness of computers, but I think that one of the underlying missions of educational institutions is to provide exposure to the different options out there.

MB: It’s not all bad, though, there is still quite a bit of support from educators. I’ll be attending the SPE conference, and that’s a great place to meet instructors from all over the country, many of whom are fighting for the same thing. I mean, just from a purely dollars-and-cents point of view, it’s pretty easy to justify the teaching of traditional photography. Enlargers will last twenty years, and it’s easy to deal with the materials. On the flip side, I hear about schools who have people whose whole job is to keep up on the licenses for the software. None of that in the darkroom.

JS: Right. Let’s spend time teaching the craft instead of keeping up on the software. The illusion of work, the illusion of learning, is no substitute for actually learning how to get things done.

MB: Exactly. You know, the history is interesting – I’ve seen old photographs from Ilford of their factory workers with tea kettles, pouring emulsion onto the glass plates. We’ve come a long way, but the technology is still basically the same.

JS: Yes. And it’s important that someone – you guys – will be keeping this technology available in the future. We know it can be a struggle. How’s the global market?

MB: Well, certainly the US is the biggest market. Europe is big, but all of our worldwide distributors are busy. There’s a big art scene in Latin America; we don’t quite have the reach down there that we would like, but the market exists. We have a good presence in Japan. Overall, it’s the US and western Europe, and the UK.

JS: What about the competition?

MB: Well, it’s the names we all know – Kodak and Fuji. And some players in eastern Europe.

JS: Who else is still active in Europe?

MB: Foma, and Bergger. Forte’s been closed for a while. There’s some activity in Agfaphoto and Ferrania. We see a little of the Oriental papers out there. We used to be the little guy, but now Ilford’s seen as the big guy. In reality, we’re a pretty small company, but we are in a growth mode.

JS: So, two big companies, then you guys, and a bunch of smaller players.

MB: Kodak has come out of the other side and are now aggressively selling films again; we’re watching this closely, of course. We’ll see how it goes for them. It’s a relatively new development.

JS: And, well, we still need Fuji, because you guys aren’t making an instant product.

MB: No – it came up when Polaroid got out of the business, and I know that there were some talks about us taking over that product line, but moving all of the equipment to the UK and dealing with the setup seemed a bit outside of our scope.

JS: So, whither the future for Ilford? The art market, of course.

MB: Well, of course, plus the education market. We think that people will be shooting film for a long, long time. There are a lot of reasons for that – the fine equipment, the ability to see the images in twenty years. I mean, everybody’s got a twenty year old floppy disk with data on it, and I challenge you to go open one and make use of it. Film doesn’t have that problem, and never will. It stores a tremendous amount of information, and we’ll be able to look at it for years to come.

JS: So, since you have the whole US territory, what’s your favorite US market?

MB: Why, Portland of course. No, really, there’s nothing like Portland. I spend a lot of time in New York – there’s so much photography there. Any of the big cities, really, there’s a lot to see. I get to see a lot of really good exhibits, and there’s so much tremendously good work going on.

JS: Let’s speak a little more about you. What did you do before Ilford?

MB: I studied photography in school and then I worked in and eventually owned a photo lab where we made Ilforchromes and did some black and white processing. That was in Austin years ago, in the 80s. I was in the lab business in Chicago, and then I was offered the job at Ilford – I had roots in Texas, and that’s where the job was, so it seemed like a natural fit. I’ve been in Dallas twenty six years – I could work anywhere, but that’s where I’ve built my life. I like it a lot. Seems like a long time when you say it out loud.

JS: And how about your personal photography?

MB: Well, I still love to shoot. I love film, and I’ve always made photos – I’ve shot since I was a teenager. I thought I would be getting into newspaper stuff, and kind of learned from other people, plus community college and then four year college. I enjoy night photography, and pinhole, documentary style – that’s what I like to shoot and what I like to see. A lot of twin lens work.

JS: And what’s your rig? What kind of camera do you use?

MB: Rollei twin lens. Pretty simple, lightweight, small enough. I do have a Hasselblad, but it never seems to come out anymore, to be honest. At Ilford, we have our own pinhole cameras, the Obscura and the Titan, so I use those quite a bit. They’re a good, simple way to shoot 4×5. I also enjoy the Zero Image – I carry around a 6×6 – very lightweight and easy to deal with. Going back to what we were talking about before, I rarely shoot much 35mm; these days, it’s primarily 120. With all this, I still really like to look at photography. I enjoy galleries, and being able to get out and look at work. You have a pretty strong gallery scene here in Portland, yes?

JS: Oh, yes. There’s a lot of action in town. More than we can attend, really. You should schedule one of your trips for a First Thursday or First Friday – we can show you around a bit.

MB: Good idea. I find it very encouraging. I guess the big message is that film photography is alive and well. While it’s smaller than it was twenty years ago, it’s still very vibrant and important. And it will be for a long time to come. Also, people should print. That’s what’s important about the darkroom – it means that people are making physical prints. I look around at the internet and phones and all, but there’s nothing like holding a beautiful print, or having one hanging on the wall – nothing like it.

JS: Photography has changed a lot since you started.

MB: Oh, yeah. A lot. Twenty years ago, I didn’t have the imagination to see where all this was going. The way I look at it now, it’s just that we have more tools. The more tools that an artist has, the better it is, but you don’t want to throw away the old tools just because you get some new ones.

JS: So, when you were in the lab business twenty years ago, I’m sure you had the old curmudgeons, the same as I did – folks to learn stuff from, and they probably complained a lot. So, back in the day, what were your curmudgeons pissed off about?

MB: Oh, the same as now. All about format. 35 was introduced so many years ago, but you would’ve thought that it was some new thing. The old timers that I used to talk to still shot their Graflexes, and stood by the quality of their sheet film. Also the same as today is the materials – even then we were losing a lot of the historic papers, the single weight fibres and so forth, and that’s always been an item of contention. We have lost a lot of really beautiful papers. The old Agfa Portriga was a beautiful paper, but even it changed – it certainly wasn’t the same paper at the end as when it started. But it’s nostalgia, really, and romance. I mean, I loved a lot of the old papers, but I wouldn’t trade them for the modern papers that we have today. The DMAXs are nice, the consistency is good, the contrast is good. I have a lot of old 70s papers, and they still look good; it would be nice if we still had a big enough market to have that kind of variety, but I’m proud of Ilford for keeping a good selection of materials available.

JS: Yes, thank you. Keeping three fibres and an RC, all in different surfaces, plus the Fine Art, is still a pretty good selection. And in a lot of sizes.

MB: We don’t make some of the large sizes anymore, but we are selling big FB paper in rolls – we offer a 50″ roll of fibre that does very well.

JS: You sell a 50″ roll of fibre?

MB: You’re darn right we do. Quite a bit of it.

JS: Who’s using it?

MB: Certain edition printers. In the past few years, in galleries especially, I’ve seen big prints becoming more and more important. Another product line that we make which is important, and it’s another niche but still important, are fibre and RC papers for hybrid printers. Laser digital enlargers use these, so we have a good line of paper that will make good darkroom silver prints from digital files. It’s just one more thing we’ve done to make our products available to the most number of people.

JS: I’m always fascinated by people’s darkrooms. You’ve been around a lot – what’s the best darkroom you’ve ever been in?

MB: Well, it’s interesting about darkrooms. I once saw someone speak about darkrooms, and his point was that darkrooms always tell stories about who is working inside them. And his other point – gosh, I wish I could remember his name – his other point was that the best darkroom is the one where you know where everything is. I mean, I love my darkroom at home, because I’m the only one who uses it – everything is always right where it should be. I don’t know if I could pick out a favorite, but I have been to some really fantastic darkrooms. There is a school in Philadelphia that recently built a new facility and I was stunned at how beautiful and well-thought-out it is. I went to one in San Diego – the city college there and the facilities were incredible. Then there’s Columbia in Chicago – they have quite a view. When you’re out there flattening the prints you’ve just made in the darkroom, the window in the workroom looks out over Lake Michigan and Michigan Avenue. That was pretty spectacular. We have a website called local darkrooms dot com – we’re using to try and help people connect to darkrooms. There are a lot of people shooting film who no longer have access to darkrooms so this website is a clearinghouse for places where you can print. If you’re traveling, you can see if there’s a rental available, or sometimes, people will even invite you into their personal darkrooms. It also has places where people are teaching traditional photo workshops and things like that. Anything we can do to help sustain the community. Globally and locally.

JS: OK, so I want to build a brand new darkroom, from scratch. What should I be thinking about?

MB: Well, for me space is a big one. I’ve seen some small darkrooms that work well, but it’s not ideal. I mean, that’s how I started, probably like you – with the table over the tub and the enlarger on the toilet, but if you can have the space, that’s the best. I never even had a real darkroom sink until I redid my darkroom about ten years ago, and I love that sink. It’s really beautiful and it makes all the difference. Just having a six foot sink, if you can have that, it’s the best thing.

JS: So you built a brand new darkroom ten years ago? Right when digital was really starting to kick?

MB: Yeah, well, I hope I have a lot of printing time left in me, I mean, I hope I’m printing in twenty five years. Probably like everybody else, I have a lot of negatives that I’ve never printed. I see my retirement as being me looking through a lot of the old stuff and playing catch-up. Plus, there’s just something about being in the darkroom. It’s somewhat intangible, but that’s what I love about it. You’re alone, you have time to think, you’re doing something with your hands. You don’t feel the same way when you have a beautiful print that came off the inkjet printer.

JS: Yeah, we have that discussion a lot – the difference between handmade and mass-produced, and it rankles the inkjet printer guys. Their point is “Well, I’m touching it, isn’t that handmade?” And my point is that if you can push a button and make ten of them, then it’s mass-produced. It’s really hard – effectively impossible, really – to make identical prints in the darkroom.

MB: Well, when we were kids and coming up, I mean, we never thought about computers being able to do it for us, right? Darkroom is the craft I came up with and I want to stick with it. It’s fascinating to meet someone who is just now in college – eighteen or nineteen years old – who’s never known not having a computer in the house. It seems to me like a lot of them really take to being in the darkroom and it feels like they’re making something. It’s like making something in a workshop. There is something about getting your hands wet.

JS: That’s a great point to end on. Anything else you’d like to address?

MB: We’ve covered a lot, right? Listen, when you asked earlier if there’s anything that I want people to know, it’s pretty simple: there’s still a lot of film being made, there’s still a lot of film being shot, and Ilford has a very long-term plan for the future. Thanks for having me, Jake – this was fun.

JS: I really enjoyed it, Mike. We’ll hope to see you again soon. Thank you, and good night.