Three Indigenous Photographers Share Their Thoughts on Film, Identity, and Their Creative Process

Photograph by Kali Spitzer.

One thing that was affirmed for us in the year 2020 was the importance of making. Through creative making we expand our ability to synthesize new ideas, allowing for growth, for forward momentum. What feels perhaps even more important moving into this new year, is to prioritize observation, learning, and listening within your creative practice. To be a great photographer requires a commitment to observation and reflection. To observe and engage with the art of another broadens our own perspective, it inspires and informs our own ways of meaning making moving forward.

We begin this new year with a feature, highlighting three Indigenous film photographers actively making, documenting, and shaping our creative and cultural consciousness. Many people have referred to this past year as an ‘apocalypse’ of sorts; from rampant global climate crises to the coronavirus to cultural revolution. As we move forward from this informative year, let's remember that this was not the first year of devastating pandemic for Indigenous communities. This was certainly not the first year of bearing witness to widespread environmental depredation. Indigenous people across the world, and specifically on Turtle Island, have been persevering for centuries through waves of apocalypse brought about by settler colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism.

We want to recognize the powerful resilience and resistance of the Indigenous peoples of these lands and we are honored to use our platform to feature these incredibly talented creatives. We hope you are inspired to seek out and support more of their work, as well as other Indigenous artists. We hope this feature inspires you to share stories from your own culture, to (re)connect to your cultural roots and to honor these through the photographs you create. We encourage you to seek out artistic expression from outside of your culture, to hold space for all the differences and similarities you may find. Here’s to practicing receptivity! Here’s to welcoming a new year by making space for new paradigms! Here’s to unlearning and to the thoughtful creation bound to come out of this expansive process!

Multi-media collaboration between Kali Spitzer and Bubzee.

Kali Spitzer is a photographer living on the traditional unceded lands of the Tsleil-Waututh, Skxwú7mesh and Musqueam peoples. Her work embraces the stories of contemporary BIPOC, Queer and trans bodies, creating representation that is self determined. Kali’s collaborative process is informed by the desire to rewrite the visual histories of indigenous bodies beyond a colonial lens.

Kali is Kaska Dena on her father’s side (a survivor of residential schools and canadian genocide) and Jewish, from Transylvania, Romania, on her mother’s side. Kali’s heritage deeply influences her work as she focuses on cultural revitalization through her art - whether in the medium of photography, ceramics, tanning hides or hunting.

Kali studied photography at the Institute of American Indian Arts and at the Santa Fe Community College. Under the mentorship of Will Wilson, Kali first explored alternative processes of photography. She works with film in 35mm, medium, and large format, as well as wet plate collodion process using an 8x10 camera.

Kali’s work has been featured in exhibitions at galleries and museums internationally including, the National Geographic’s Women: a Century of Change at the National Geographic Museum (2020), and Larger than Memory: Contemporary Art From Indigenous North America at the Heard Museum (2020). In 2017, Kali received a Reveal Indigenous Art Award from Hnatyshyn Foundation.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Josué Rivas, of Mexica and Otomi lineage, is an Indigenous Futurist, creative director, visual storyteller and educator working at the intersection of art, journalism, and social justice. His work aims to challenge the mainstream narrative about Indigenous peoples, and to build awareness about issues affecting Native communities across Turtle Island. He seeks to be a visual messenger for those in the shadows of our society.

Josué is the co-founder of NativesPhotograph, a visual database established to elevate the work of Indigenous photojournalists. Their mission is to support the media industry in hiring more Indigenous photographers to tell the stories of their own communities and to encourage Indigenous sovereignty in the ways in which their stories are reported on and shared out with the world.

Josué is the founder of the Standing Strong Project, made possible in part by the 2017 Magnum Foundation Photography and Social Justice Fellowship. He is a 2020 Catchlight Leadership Fellow and winner of the 2018 FotoEvidence Book Award with World Press Photo. His work has appeared in National Geographic, The Guardian, and The New York Times, amongst others. He is available for photo assignments, film projects, and exhibitions. He is based right here in Portland, OR.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Evan James Benally Atwood is a self-identified nádleehí* Diné photographer and artist born to Ta'neeszahnii (Tangle clan), Áshįįhí (Salt people clan), Naakai Dine'é (Mexican clan), and Bilagáana (English/Welsh) residing in the ancestral lands of the Chinook tribe (portland, or).

Evan’s work is playful in its vulnerability. It is intimately personal and driven by a clean, precise aesthetic. Their work is an invitation to the viewer to look inward, to reflect and connect. Their work grows out from and along with the intersection of queer identity and honoring their ancestral Dinê lineage. By pairing this foundation, along with passionate collaboration within queer and indigenous feminist communities, they use photography and film to document stories and uplift marginalized voices with the intent to inspire others in shared communities. Their work has appeared in TIME magazine, Vice Broadly, and at the Smithsonian Native Cinema Showcase in New York, among others.

* nádleehí is a Diné gender descriptor for an effeminate masculine bodied person

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

BMC: Why do you incorporate film into your creative process? Is there anything about the medium itself that resonates with you as an artist?

Kali: I work in all analog processes. I feel that 35 mm, 120 and large format wet plate collodion offer a richness to both the final image and process that you can’t achieve with digital photography. The richness and beauty comes in part from the imperfections that are created through this tactile process. Being able to make your own film and hand pour creates an element of connectivity that I couldn’t find within digital photography, there is also a relationship with time and pace that is not part of a digital photography practice. You have to trust yourself more with film because you can’t see the finished product until you develop it, there is more room for intuitive decisions.

Josué: I grew up around film, both my parents are photographers. It wasn't until my early twenties when I picked up my father's camera that I came to remember the healing power of images. For me, working with film is a completely different vibration in comparison to digital. Working with grain instead of pixels gives me the opportunity to slow down and be more in tune with the frame. Working with film allows me to fully focus on the moment and be present.

Evan: My business card says Diné, Queer, Creative. I don’t include the label of filmmaker, director of photography, or any specific thing. My scope is larger than any one thing, it’s spirit-led. The intention is there between me and the camera. It’s my tool. You can’t just give it to another person and have the same feeling. In the Indigenous way, it’s a mystery. My camera is a thrifted one from 1972. I have another from 1964, and there’s something about these old rangefinder cameras–you have to get intimate with these cameras, different than with a digital camera. The analog way has forced me to be intentional in my photos, because you don’t get a bunch of shots. There's a relationship built with each camera's functionality and ability to help visualize feelings. Photography can be a conversation and document connections, rangefinders make me spend more time on less photos, I love all parts about it.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

BMC: One special thing about film is that there is a tangible artifact left behind - the negative, the physical objects that culminate to make the photograph... What do these artifacts look like for you in your process? Do they hold any particular meaning for you?

Kali: Every step of the process is meaningful for me, the physical object is less of the focus for me and the take away is the emotional connection with the person while collaborating on the image, though it is meaningful to have physical archiving material that exists beyond the digital realm.

Josué: Recently I came across the negatives of my first rolls of film. For me, the negatives represent the physical memory of a moment or portal. They are also a starting point for an internal conversation with me as an artist.

Evan: Absolutely, the negative is physical and can be used to create prints of work, which is even more powerful. Photography is a way of getting to know myself, too. When I take photos of myself, it’s an intimate experience. Cowboy Juice is definitely introspective. I came to Oregon and realized I could create with clothing, put items together. I searched through other people’s trash and found things they didn’t want. I was styling myself. It’s intimate and provocative. Through that project, I could be the person I saw in my head, envision new versions of myself and document forms. It’s so personal—it’s my ass in your face, and you’re going to look at it. Maybe you’ll feel something. Doing it helped me love my body. Just the act itself. Creating it allowed that space to exist. It’s definitely funny to put on these assless chaps out in the desert and put a 10-second timer on your medium-format camera (mamiya 7) that you gifted yourself because you deserve it and go out and pose for photos. There’s totally joy, humor, and lightheartedness in that. It feels like a form of visual sovereignty. A person can rip a printed photo of Cowboy Juice in half, and I can print another one. The photo still exists. There’s a queer Native person on this Earth, and you can’t do anything about it—we exist.

Tin type by Kali Spitzer.

How is your photographic process informed by your culture? How is your notion of identity-making informed by your experience as an indigenous person?

Kali: Historically, photography has been used as a violent colonial tool. I am working with a century old process to reclaim and rewrite our relationship to photography as indigenous people. The values I was raised with are present in the way I work, integrity and intentionality are the founding pillars.

Most of my work directly comments on identity including culture, sexuality and gender. I am providing space for authenticity, for people to be heard, seen and represented accurately. The ability to slow down through the use of film enables me to build a relationship of trust and intimacy with the person I am collaborating with.

Josué: My identity is the foundation and serves as a guide for my work. Whether I'm documenting Indigenous movements or creating spaces for us to tell our own story, my ancestors stand behind me and my descendants in front of me. My practice is also guided by the understanding that we as Indigenous peoples will exist in the future; I believe we are in a moment where telling our own stories and reclaiming our narrative is a first step towards re-imagining what that future looks like. Technology will shape visual storytelling and I think Indigenous peoples will be at the forefront of that transition. My hope is that our identity will continue to serve as a reference point for now the stories we tell as future ancestors.

Evan: I read this book 'Through Navajo Eyes' by s. worth (72) and found the "anthro" perspective more respectful than some recent settler approaches to my existence. They teach 16mm to 6 Diné students and what they've made in the end is 120 mins of black and white film. It can be viewed as its own form of communication, film as Diné bizaad (Navajo communication). I honor this approach the students take in their processes and do my best myself to hold people in my photographs. Identity plays a roll [sic] in my work simply for existing as a queer brown body, documenting forms, documenting my love for the community around me. When I document my community, it's from my heart and openness to the experiences of everyone around gender. In an Indigenous way, gender is thought of psychospiritually, where western society only thinks of gender physiologically. The ideas around the latter halts the beautiful balance of femininity and masculinity in ourselves. These days, we must accept change is inevitable, human life isn't meant to be static. Transgender humans are the bravest, kindest, wholeheartedly beautiful I know and I'll do my best in my work to honor that. I enjoy the act of creating joy, documenting joy, especially with queer Black, Indigenous, POC creatives.

I talked to a Diné elder friend Larry King recently about his experience around the word nádleehi (a Diné gender descriptive for an effeminate masculine bodied person) and having been in school in the 1960s, he said it was used derogatively as if to say “you don’t belong here.” I say this to emphasize the teaching of hatred is rooted in the american way, taught through assimilative tactics, within the education systems.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Photograph by Kali Spitzer.

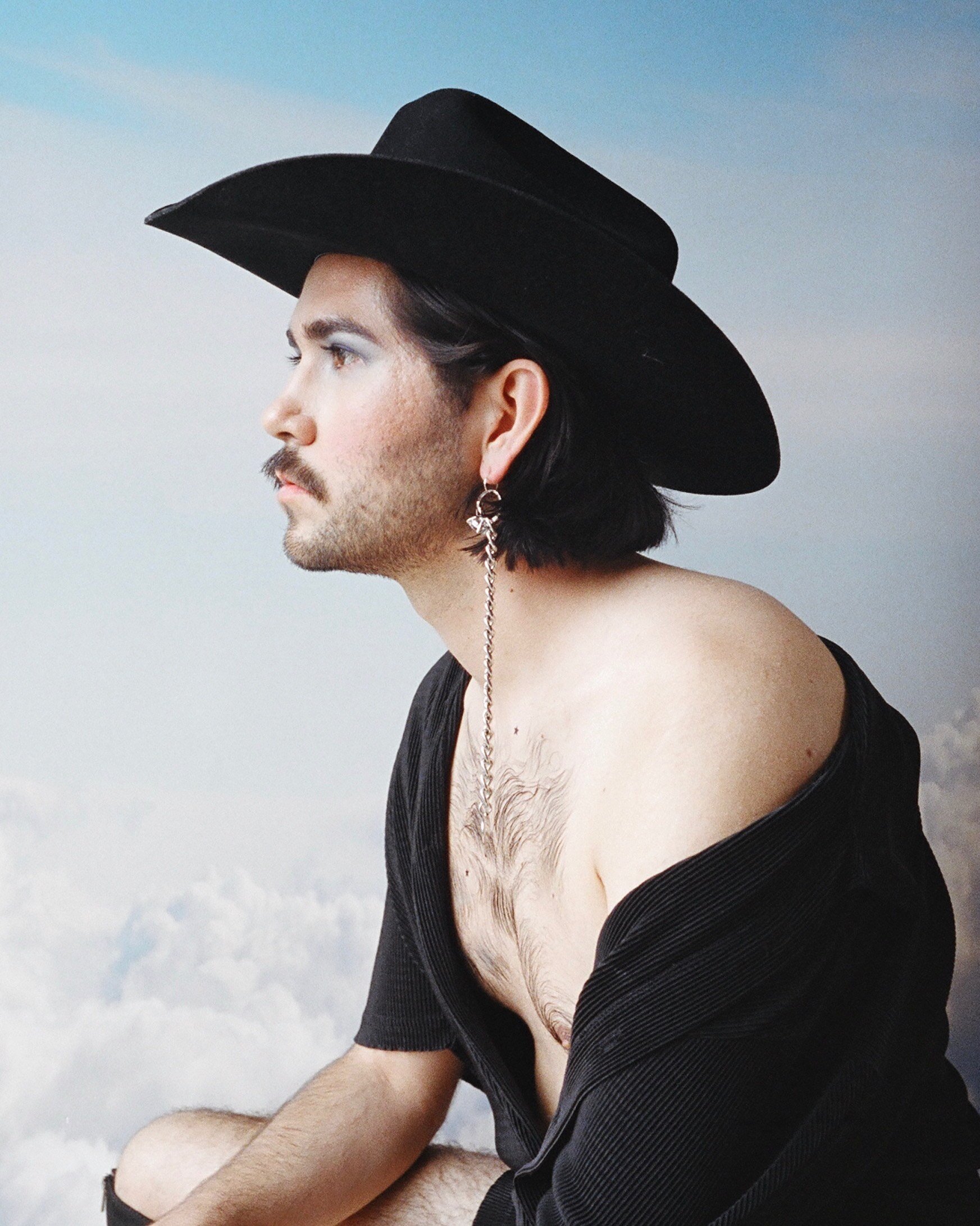

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Photograph by Kali Spitzer.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.

Photograph by Josué Rivas.

Photograph by Evan James Benally Atwood.