Resolving to Understand Scan Resolutions

Written by Zeb Andrews

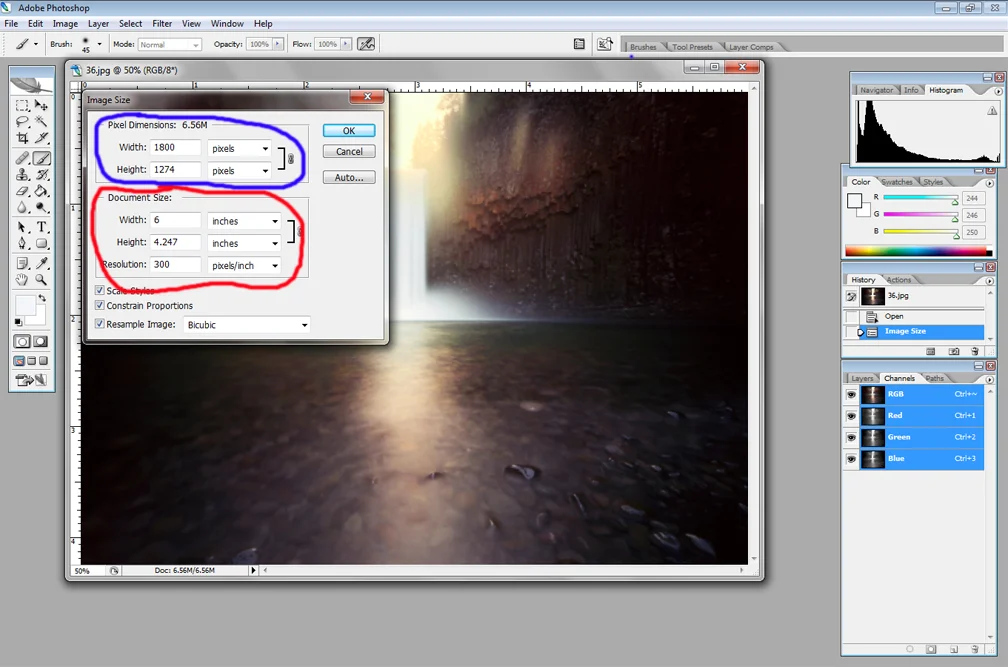

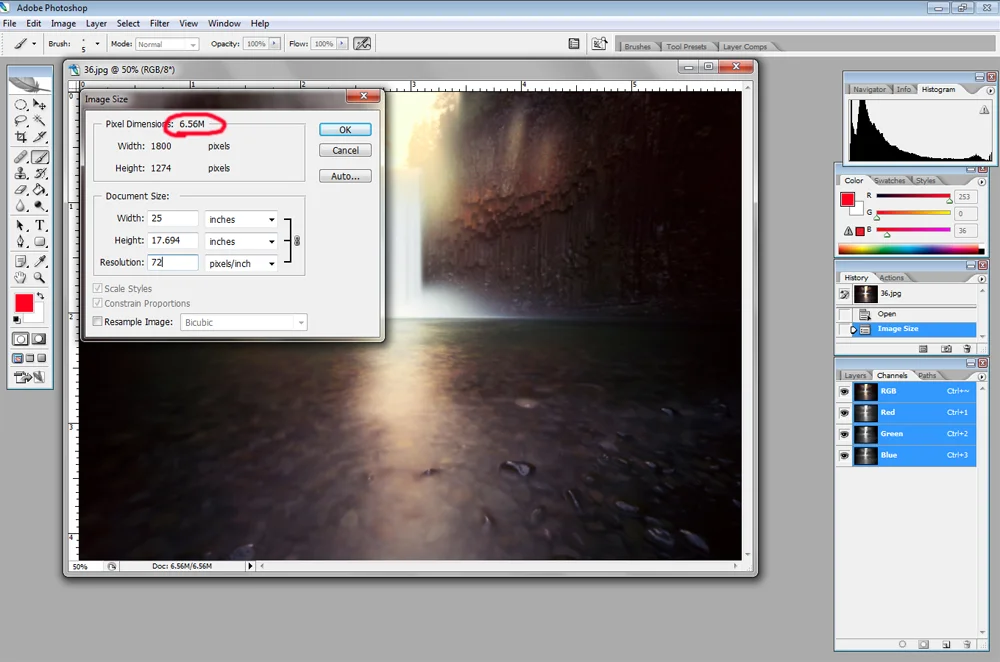

Both images are sized to the same length and width but at different resolutions.

Resolutions.

It seems they are either causing undue amounts of New Year’s-related angst or they are sending photographers into circles of confusion. Well, we can help you with one of these problems (you’re on your own with that new diet come the new year).

Let’s start simple. When we are talking about the resolution of a digital file – originating either from a DSLR or from a film scan – we are talking about a unit of measurement. Much as you would use length and width to note how large a rectangle is, you use length, width and resolution to express the size of a digital image. That’s right, digital images require three measurements. Length and width are fairly self-explanatory, so if it helps, think of resolution in this case as density, or how much information is packed into the image. I would like to take just a moment to emphasize the need for all THREE measurements. If I ask ten photographers to give me an image sized to 8×10 inches it is entirely possible for each to ultimately give me different sized files by virtue of different resolutions. They may all have lengths and widths that match my instructions but one image may have a resolution of 72 while another is set to 300 and so forth – see the opening image above for the difference this can cause.

So what exactly does this nebulous resolution number mean? Generally it is expressed as “ppi” (pixels per inch) though “dpi” (dots per inch) is commonly used as well. The more pixels/dots you have per inch, the more dense the information in your image. So a resolution of 72 ppi means many fewer pixels are crammed in per inch than say, 300 ppi, which also means a print made from a 4×6 inch 72 ppi file is going to have less small detail and look more pixelated than a print made from a 4×6 at 300 ppi.

Resolution can be expressed with any number you can think of, which may seem overwhelming at first, but like length and width we can narrow that infinite number of possibilities down to a few popular choices: 72 and 300. In short, 72 ppi is the resolution your images should be set to whenever they are going to be displayed on a computer screen, be that destination e-mail, Flickr, Facebook, Tumblr, you name it. If it is on the web, then 72 is your number. I know some of you in the audience want to raise your hands at this point to remark that this is not entirely true, that computer monitors can display at a variety of resolutions, but for the sake of simplicity and brevity, stick with 72 as a benchmark number. A 300 ppi resolution is used for printing. So whenever you are making a print to hang on the wall or put in a scrapbook album, you will size the image according to your desires and set the resolution to 300. As with monitors it is true that not all printers output at 300; some suggest using 250 or 225 or even 200, but again as a general (and simple) rule of thumb, if you stick with 300 for printing you will always be fine.

Additionally there is little to no benefit from using a resolution higher than either 72 or 300 for their respective uses. Printing an 8×10 at 800 ppi will not result in a more detailed print than an 8×10 at 300 ppi because printers generally only output up to 300 dpi so anything beyond that is unused information. Likewise, a 5×7 image on a computer screen at 72 ppi looks just as nice as a 5×7 at 300 ppi because monitors are not capable of showing more than 72 pixels per inch. So while it is true that using a lower-than-adequate resolution will negatively affect the quality of your images, using a higher-than-adequate will not result in any benefit.

So far so good? A couple of examples, perhaps? Let’s say Theresa gets an awesome photo of sunset at the beach and decides she wants to make a giant print for her wall which she is going to mat and frame and stare at proudly for years. She settles on a 16×20 print as the size she wants, so she preps the image for her printer by cropping it to 16×20 and makes sure the resolution is set to 300, she saves the file and sends it off. A couple of days later she picks up her new print and it looks gorgeous. She then decides she is going to post the image to her Facebook account so her friends and family can enjoy it. She figures that an 8×10 on a computer screen is large enough and sets her resolution to 72 and saves this as a new file (not wanting to overwrite her much larger original with this smaller version) and uploads it to Facebook. Voila!

Now let’s take a gander at an image size editor. The example below uses Photoshop, but Lightroom, Aperture, or most any other image editor will have a similar interface.

The size of an image can be expressed in one of two methods, either through pixel dimensions or through document size. Pixel dimensions is a bit tidier as it uses only length and width (but measured in pixels, not inches). In terms of data, this is a cleaner approach. The problem with pixel dimensions is that most of us don’t think in those terms. You don’t look at a 16×20 on the wall and say, “that image looks great as a 4800 x 6000 pixel print.” So most photographers tend to prefer document size. By the way, pixel dimensions are calculated by taking the length or width of the document size and multiplying it by the resolution. So our 6 inch 300 dpi image in the example above has a pixel dimension of 1800 pixels on its long end.

Ok, now I am going to throw a curveball your way.

Notice in both examples how my file size is 6.56M (as circled in red in the second image). Also notice how the pixel dimensions remain the same in both images. But look at the document size, in the upper version we have what amounts to a 6×4 at 300 ppi but in the bottom image we have 25×17.7 at 72 ppi, yet according to the pixel dimensions they are the same size. As mentioned above, resolution is like density, so the thinner we spread it, the large an area it can cover. Look at it this way; I give you a ball of clay and ask you to roll it out for me into a 4×6 rectangle. Once done, you measure the thickness and find that your clay rectangle is fairly thick. Now I ask you to roll that clay out into a 18×25 inch rectangle, which produces a very thin result. The amount of clay overall has not changed, you have just spread it out thinner and over a larger area. Document size works the same way. The same file in this case can produce a 4×6 inch 300ppi print or it can make an 17.7×25 inch 72 ppi image on a computer monitor. It is important to remember this because even though an image may have a resolution of 72 ppi, this one number by itself does not mean the image is low resolution. An image of 72 ppi and a length of 60 inches has a pixel dimension of 4,320 pixels (72 x 60) which is the equivalent of 14.4 inches at 300 ppi (14.4 x 300 = 4320 pixels). This throws some photographers off because they think that 72 equates to low resolution, but I remind you that it takes all three measurements used in conjunction with document size to fully express how big a file is. Even a low resolution number coupled with very large lengths and widths can still make very large prints and therefore be a high resolution image.

In summary, it is important to remember that document size requires length, width and resolution. A resolution of 72 ppi by itself means very little without an accompanying length and width, likewise a length and width without a resolution is equally incomplete. Keep your resolutions narrowed to two numbers: 72 for computer screens and internet and 300 for printing. Juggling only two numbers is much easier after all. Finally, bear in mind that these numbers are flexible; an image 1800 pixels on a side can be either 6 inches at 300 ppi or 25 inches at 72 ppi. Hopefully this is now one less type of resolution you have to worry about. Best of luck to you on those other ones that pop up come January 1st.